Vibrato

A discussion concerning vibrato

Vibrato comes from the elbow, whether it is called arm, wrist, or finger vibrato. These are misleading terms, as people tend to think that they refer to where the vibrato originates. They do not; what the second and third terms mean is that the joint being referred to takes a greater degree of flexibility when employed, producing a varied speed and amplitude particular to that joint’s flexibility. I have seen people demonstrate “wrist vibrato” that was nothing more than the rotation of the 2 bones of the forearm coming from the elbow. Bernard Greenhouse would occasionally employ something close to a true wrist vibrato (moving the hand from the wrist joint) but he employed this very infrequently, only on certain notes of a phrase, and only in lower positions. A very particular color of sound, and not how he normally employed vibrato.

Many other fine cellists sometimes play with the thumb released from the neck, and it is not at all controversial (though some pedants may say so). Look at videos of any cellist whose sound you are fond of. Chances are good that they will release the thumb at least occasionally. The thumb has nothing to do with the vibrato, and it is, if anything, usually the source of trouble when someone has a problem with vibrato.

Vibrato is only very rarely from the rotation of the hand, as the range of speed of oscillation in this manner is very limited. The most flexible vibrato originates from the forearm/elbow, which allows for the greatest range of speed of oscillation and greater ease of connection of the vibrato from note to note. Any forearm rotation that occurs should be incidental. It is always most efficient to use the largest possible muscle for the action at hand, as there is less energy and effort required to move a large muscle by a small amount than a small one a large amount, so by using the forearm to initiate the vibrato, this efficiency is possible. This concept of muscle use is an important aspect of Casal’s legacy.

In order to produce a “legato” vibrato, one that continues evenly from finger to finger without interruption when playing a melody, it is necessary to have a very consistent balance of the weight of the arm and hand regarding the finger that is playing. The thumb can be used as a pivot point, or can be released from the neck entirely as one gains greater mastery. Putting the fingers down is not just about using muscles to place the finger, it also includes a slight rotation of the forearm (and hand) so that the arm weight is balanced on the finger that is playing. To include vibrato with this action, one must first have consistent control of this balance. As vibrato is the linear action of the forearm that moves the finger pad down and up the string to change the pitch fractionally, it must be carefully coordinated with the action of placing the fingers. Ideally, the motion of vibrato is independent of that of placing (and displacing) of the fingers on the string such that it can be continued even while the fingers/notes change, creating a consistent quality of sound (and therefore easily varied) through any phrase as desired. The other benefit of this is a very relaxed and flexible left hand, as you cannot achieve this consistency with much tension in the hand.

As arm vibrato comes from the elbow, and pitch change on the cello is linear (following the line of the string), it is necessary that the act of vibrato is also linear. The motion of vibrato is not unlike shifting, in that the forearm moves the hand up or down the fingerboard parallel to the string to effect change in position/pitch. As vibrato is a subtle change in pitch, the motion is much smaller than when changing positions. The basic motion is a slight closing and opening of the elbow that allows for the fingerpad to move slightly on the string to alter the pitch. It is most often taught that the finger first establishes the pitch in its initial contact with the string and then descends and returns to the pitch. How wide the change in pitch is is determined by the amount of the fingerpad that comes in contact with the string. Some people have huge fingerpads (like Bernard Greenhouse or Lynn Harrell), so there is not a lot of motion required to accomplish this. Other people have considerably smaller fingerpads, which requires more considerable motion in order to create a similar amplitude. In general, having the hand at a slight angle, such that the base knuckle of the 4th finger is a bit further from the string than that of the first finger (this is as opposed to that school which suggests that the base knuckles be parallel to the string) is better. There are a number of reasons that for most people, the former is a superior approach, but I will not get into that here. As regards the angle of approach of the hand to the fingerboard and vibrato, having this angle in place makes a wider fingerpad contact with the string possible. You can start with the edge of the tip of the finger on the string and descend across the fingerpad at an angle across it, maximizing the area of contact and therefore the amplitude of the vibrato. To move the fingertip on the string, you need both the knuckles of the finger and the wrist to be flexible, as you pull and push the hand from the elbow (NOT the shoulder). This should be done very slowly and sound like a glissando, not 2 distinct pitches, top and bottom. It is a good idea to do this with a metronome to practice this in slow motion (not just slowly). Try the metronome set somewhere between 40-60 bpm and imagine that you are playing half note for the top and a half note for the bottom of the pitch. Bear in mind that you never sit on either the top or bottom pitches, you are always in motion. 4th position is a good place to begin. Remember, you are NOT rotating the forearm at all. You are pulling and pushing the fingertip down and up the fingerboard (“pumping” is how Paul Katz describes it in the video example below). Once you can do this easily on all 4 fingers, then make each pitch a quarter note, then 1/8th note, triplet 1/8ths, 1/16th notes, and setuplet 1/16th notes. There is an exercise in Diran Alexanian’s book (available at IMSLP.org) along these lines, though the explanation is not always the most clear. The thumb cannot be tense or stiff, indeed you can see that Yo-Yo Ma (and many other excellent cellists) often plays without his thumb. The thumb is at best a point of reference for the hand, there to guide the fingers and the rotation of the forearm that channels the weight of the arm into the fingers. Pressing with the thumb will only do harm to your playing and limit the freedom of motion of the vibrato

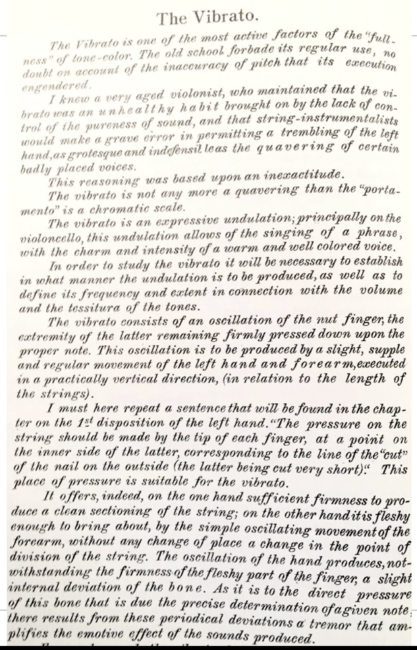

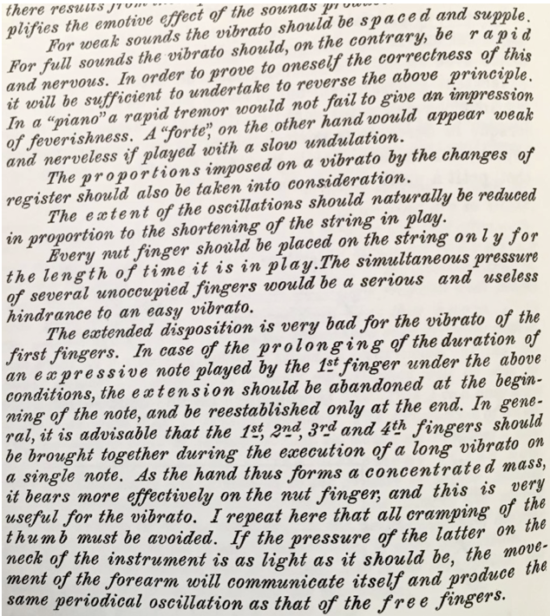

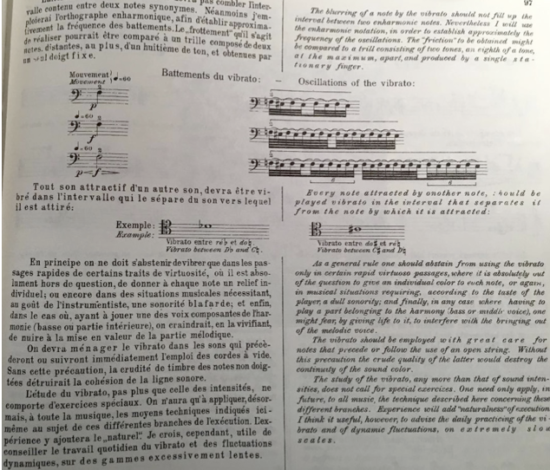

Diran Alexanian on vibrato

In learning to vibrate, it is useful to understand that the goal you are reaching for is a relaxed and balanced left hand, so that as you develop a vibrato motion, one must not lose sight of this.

Vibrato in slow motion (scroll down for the cello)

https://www.thestrad.com/6884.article

I have never seen a study such as this that any real scientist would look at and say that it proves something. From what I have seen, these are all flawed in their design. The current authors in question have published other such “studies” before, and while I am certain they are quite sincere in their intent, the results are problematic to me.

In this paper, the vast majority of the oscillation is below the pitch, and if you were to crunch the numbers of the frequencies for either mean or average frequency, it would be below the pitch center intended, not equally on both sides of the pitch which the authors seem to suggest. As to the cellist in this study, the pitch on every finger but the 4th is placed sharp of the intended pitch in the unvibrated note, but thereafter the range of frequencies within the vibrato has what appears to be the same pattern as the violinist. Because it starts sharp, it appears on the graph as being centered on the pitch. Again, if you were to crunch the numbers, it would have the same effect as with the violin, only it would be sharp to the intended pitch because it started out sharp. While this study intends to prove that vibrato is symmetrical around the intended pitch, it fails to accomplish its aim for these reasons.

In one of David Finckel’s videos on the topic, he slows down Fischer-Dieskau singing to study it for speed, width, and relation to pitch. Sounds pretty awful to me slowed down, kind of nauseating. I personally was more enraptured by his nuance (the variety of vibrato) and “musicality” than by his intonation or tone. I found it interesting that when Finckel demonstrates a vibrato in another of these videos equally on both sides of the note (below), he quickly adjusts his finger such that the top of the oscillation pitch goes down a fraction and THEN sounds in tune (at least to me). He makes the vibrato so that the top is only slightly above the pitch. This is consistent with the observations I made of the study above.

To me the controversy is not so much “is it only below the note,” or “equally on both sides of the pitch,” but where the actual pitch is within the oscillation. In this most recent illustration, it is clear that the vibrato is NOT equally on both sides of the note. I practice vibrato every day that I play as part of my warm up, and I focus it on below the note. However, as each person’s hand and finger shapes are different, and each finger does approach the string slightly differently, where the note starts is more dependent on that than anything else (rather than the vibrato’s focus). In my case, my 4th finger curves slightly back, compared to the others, so that when I place that finger on the string it is the upper part of the fingerpad that lands first and the vibrato goes down from there. It may well oscillate slightly above thereafter, but that is the initial action.

Here is a short discussion of vibrato with Paul Katz. He talks about Greenhouse’s approach, which I would amplify a bit. The “angled” approach allows the vibrato to be initiated from the elbow (no involvement of the shoulder whatsoever). Greenhouse used many variations on this gesture to color the sound with variety; more/less flexibility on the finger alters amplitude and speed, as does a more active wrist, etc.

Katz on Greenhouse and hand positions with vibrato:

Another aspect of vibrato involves sum and difference tone math, which accounts for why vibrato makes an instrument (or voice) sound louder. Yes, it’s true! Consider that in the later classical era, when concert halls became more common for the public performance of music (rather than in churches or the residences of nobility), vibrato became much more common because those making use of it were heard more easily. Those singers and string players who employed it projected better into the larger spaces of these new public arenas, and as a result, others soon adopted the practice. The reason that this is so is that the vibrato creates many more complex waveforms in the sound (more “sum and difference tones”) that literally make more sound, as well as more reflected sound (ambience) in the hall. In stringed instruments, this creation of more sound begins within the body of the instrument itself (more complex waveforms within the instrument) as well as how those more dense soundwaves fill the hall.