Cello terminology and building technique

There is some ambiguous and/or inconsistent language traditionally employed by cellists in reference to aspects of cello playing. For instance, I define positions as they are commonly understood and have been as far back as I see method books (Duport, Dotzauer, et al), yet there are some in eastern Europe who refer to positions chromatically (Starker occasionally did this as well). There is a certain logic to that, but most of the world uses the diatonic system of reference. However, while I have never heard anyone refer to “2.5 position” for instance, we do say “half position.” Yes, it is inconsistent. If you are playing in Eb minor and you have your left hand on the notes Eb (1st), F (3rd), and Gb (4th) above middle C on the A string, it is 4th position, not 3.5 position, for instance, nor is it an “extended” position. In “normal” thumb position with the thumb on the A above middle C, you are in 8th position because the 1st finger is on B, the 8th diatonic note above the open A string. Ah, ambiguity!

One example of the misuse of language in referring to how the cello is played is “supination,” a term commonly used by Starker (and many others) in reference to the bow hand. If one were to supinate the bow hand, there would be silence, as the bow would be rotated away from the cello and not in contact with the instrument. We used the term (incorrectly) to refer to the condition of the hand when it is not “pronated.”

Pronation:

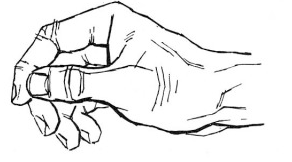

There are also some confusing thoughts about the position of the wrists, some people suggest “flat”, some others “bent.” It is important that the wrist is flexible in order to avoid tension, but a very important consideration is what maintaining any position that isn’t “neutral” puts stress on the tendons that control the fingers where they pass through the wrist as bent either up or down puts pressure on the tendons within the wrist. Here is a depiction of the wrist in neutral position.

There are lots of examples of such ambiguities in cello land. In the mid-1950s, Luigi Silva and Rudolf Matz were working on a treatise to address these kinds of issues. Sadly, it was never completed due to Silva’s untimely death. (Is there a timely death?) Such questions…

Some time ago, I tracked down Margery Enix’s book on Matz (which I finished a while back), and then I found copies of the late editions of some of Matz’s Etudes at the Soundpost in Toronto (some are also available from Shar). I had worked a bit with Lev Aronson as a child, and later visited with him a few times as a young man on visits back to my native Texas. He had come to the Berlin Ballet at the Metropolitan Opera where I was playing one summer (and was present at the infamous “murder at the Met” performance), and we were on the same flight to Dallas afterward. Lev had published 2 volumes of “the Complete Cellist” in the mid 1970s on which he had collaborated with Matz. I had several other indirect connections to Matz, as well, Aldo Parisot (with whom I studied) had worked with Matz’s earlier collaborator, Luigi Silva, and I had worked with Antonio Janigro, who was a close colleague of Matz’s for over 2 decades in Zagreb.

Matz was a great teacher and theoretician of the cello, as proclaimed by Rose, Starker, and many others. Unfortunately, it is very hard to find his music, as much has been out of print, yet is still protected by copyright (I think he passed away in 1988). Among the many young players who are his musical children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, you can count some wonderful cellists.

Matz addressed both the technical and the musical in his work, but he addressed them in parallel. His Etudes are not like Franchomme, Chopin, or Liszt, many are actually short exercises for the fingers based on the “Gemignani Grips” concept, which is explained in the Matz/Aronson collaboration based on Matz’s work in “the Complete Cellist,” and more elaborately in Margery Enix’s book on Matz. Other methods have employed similar concepts, but he was the first to deal with training a young cellist in such a way as to avoid injury (such as Focal Dystonia) through exercises based on a deep understanding of the anatomical/ physiological issues involved. At the same time, he is training the ear through the tonalities he uses, clefs, and the conceptual (as Starker makes reference to) such as the “geography” of the fingerboard. In tandem with the Etudes, he published pieces that use the recently learned (via the Etudes) techniques in a musical setting, sometimes in ensemble works for multiple cellos. In this regard, there is an inimitable relationship of technique to music. They are always intricately (but subtly) related. I suggest the 54 Etudes for young hands and 25 Etudes (lower positions) in particular.

Recently, I got out the cello after a couple weeks neglect and decided to go through some of these etudes. All I can say is wow, what great materials! Musically simple, pleasant, and succinct, they are so well considered in terms of developing technique, at least as far as I have gotten in them, including those concerned with the introduction of thumb position. There are a few small errors (missing accidentals), but they are just tremendous for what they seek to do.

I can understand why Janigro, Silva, Starker, and Rose (among others) considered him to be the greatest theoretician of the cello. It is terrible that these works are not more widely available and used. Really just fantastic tools.

https://www.facebook.com/Stac3yK/posts/10103295602059101

https://archive.org/details/Matz_CompleteCellist/mode/2up?ui=embed&view=theater

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/184868530

The following is a copy of Luigi Silva’s proposed Treatise, also available (along with many other collections of well-known cellists’ papers) from the UNCG archives.