VIOLIN STRINGS, SET UP, BOWS AND PERFORMANCE TECHNIQUES- Anne Hussay

Anne Hussay’s essay of the evolution of the violin family setup, from related ancestries and theoretical writing to the present.

Anne Hussay’s essay of the evolution of the violin family setup, from related ancestries and theoretical writing to the present.

Anne Hussay’s informative essay on the often neglected function of the string “after length” of the cello.

Eric FOUILHE1; Giacomo GOLI2; Anne HOUSSAY3; George STOPPANI4.

More research regarding the function and effect of the cello tailpiece

Ben Hebbert finds a historical gem that gives an excellent indication of the worth of Cremonese violins during the 18th century.

This article by Benjamin Hebbert offers a unique insight into the history of the violin trade, setting it within an interesting context, the parallel invention of traditions that may seem unrelated. In doing so, he brings a unique insight into the rapid appreciation of both the great violin makers’ art and the simultaneous appreciation of its value.

It is meticulously researched, clearly presented, and an entertaining read.

A study of the manner in which a tailpiece effects the sound of the cello.

https://nycellist.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/String-After-length-and-the-Cello-Tailpiece.pdf

An exhaustively researched history of the making of strings from ancient times to modern, with emphasis on the evolution of the making of gut strings.

https://nycellist.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Roman-and-Neapolitan-Gut-Strings-1.pdf

Fake cello 1

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1FmuaEx_CIQ0Fc9-LHRZgR-RDK1OOUhXo/view?usp=sharing

Fake cello 2

https://drive.google.com/file/d/15eetSFdzZVCH89yUjXzao17YctF-OAIJ/view?usp=sharing

Fake cello 3

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1lWCfaazdd6ibB7VU3N-JEmYjGh5nzikg/view?usp=sharing

The actual cellist heard is Eleanor Aller, playing first the Haydn D major Concerto Finale, and the other excerpts are from the Korngold Concerto,

To find music that is rare, or under copyright that is available for fair use, Worldcat is the international resource for searching libraries. If you enter your location, it will start with a list that is closer to you, and continue as needed. Sometimes one must pay for a scanned copy, sometimes works are available through interlibrary loan. If you copy the information from where something is located and all identifying information from that host institution (call number, file info, etc.), one can take that information to a local library and get their help in requesting the score.

Once on the page, select advanced search (a little graphic to the right of the search window), and in “format” select Musical Score, and enter title of the work you are looking for and the composer’s name (as author). Sometimes it takes a few tries to find what you are looking for (particularly the manner in which you enter the title).

How is it that a musician can introduce themselves? As the proof of the pudding is in the doing where a performer is concerned, it seems most obvious in biographical statements that are all too common nowadays that such statements as, “greatest X of their generation!” etc, and glowing reviews are the norm. Yeah, I guess there’s that. But I’m mostly retired at this point, so I’m past the “brilliantly talented!” ” a “gift to their art!” phase of life (not that I make such claims, just commenting on how this is sometimes done). So what’s left? A poet I once knew wrote a work concerning hieroglyphs which had the line, “these tiny scratches echo lives.” In that vein, what better offering in this regard than these tiny engravings of numbers within the ether of the internet, echos of a life in music.

The Arden Trio live

From old cassettes of live performances, some in concert, some from broadcasts, some incomplete. Stuff happens to old tapes…

There is some ambiguous and/or inconsistent language traditionally employed by cellists in reference to aspects of cello playing. For instance, I define positions as they are commonly understood and have been as far back as I see method books (Duport, Dotzauer, et al), yet there are some in eastern Europe who refer to positions chromatically (Starker occasionally did this as well). There is a certain logic to that, but most of the world uses the diatonic system of reference. However, while I have never heard anyone refer to “2.5 position” for instance, we do say “half position.” Yes, it is inconsistent. If you are playing in Eb minor and you have your left hand on the notes Eb (1st), F (3rd), and Gb (4th) above middle C on the A string, it is 4th position, not 3.5 position, for instance, nor is it an “extended” position. In “normal” thumb position with the thumb on the A above middle C, you are in 8th position because the 1st finger is on B, the 8th diatonic note above the open A string. Ah, ambiguity!

One example of the misuse of language in referring to how the cello is played is “supination,” a term commonly used by Starker (and many others) in reference to the bow hand. If one were to supinate the bow hand, there would be silence, as the bow would be rotated away from the cello and not in contact with the instrument. We used the term (incorrectly) to refer to the condition of the hand when it is not “pronated.”

There are also some confusing thoughts about the position of the wrists, some people suggest “flat”, some others “bent.” It is important that the wrist is flexible in order to avoid tension, but a very important consideration is what maintaining any position that isn’t “neutral” puts stress on the tendons that control the fingers where they pass through the wrist as bent either up or down puts pressure on the tendons within the wrist. Here is a depiction of the wrist in neutral position.

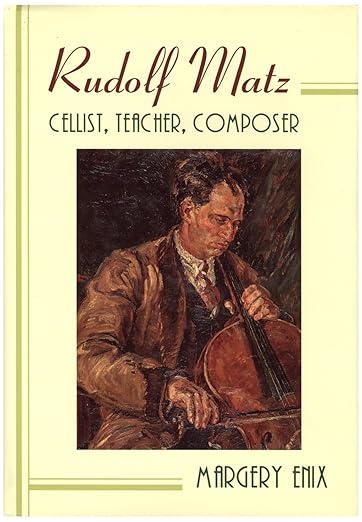

There are lots of examples of such ambiguities in cello land. In the mid-1950s, Luigi Silva and Rudolf Matz were working on a treatise to address these kinds of issues. Sadly, it was never completed due to Silva’s untimely death. (Is there a timely death?) Such questions…

Some time ago, I tracked down Margery Enix’s book on Matz (which I finished a while back), and then I found copies of the late editions of some of Matz’s Etudes at the Soundpost in Toronto (some are also available from Shar). I had worked a bit with Lev Aronson as a child, and later visited with him a few times as a young man on visits back to my native Texas. He had come to the Berlin Ballet at the Metropolitan Opera where I was playing one summer (and was present at the infamous “murder at the Met” performance), and we were on the same flight to Dallas afterward. Lev had published 2 volumes of “the Complete Cellist” in the mid 1970s on which he had collaborated with Matz. I had several other indirect connections to Matz, as well, Aldo Parisot (with whom I studied) had worked with Matz’s earlier collaborator, Luigi Silva, and I had worked with Antonio Janigro, who was a close colleague of Matz’s for over 2 decades in Zagreb.

Matz was a great teacher and theoretician of the cello, as proclaimed by Rose, Starker, and many others. Unfortunately, it is very hard to find his music, as much has been out of print, yet is still protected by copyright (I think he passed away in 1988). Among the many young players who are his musical children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, you can count some wonderful cellists.

Matz addressed both the technical and the musical in his work, but he addressed them in parallel. His Etudes are not like Franchomme, Chopin, or Liszt, many are actually short exercises for the fingers based on the “Gemignani Grips” concept, which is explained in the Matz/Aronson collaboration based on Matz’s work in “the Complete Cellist,” and more elaborately in Margery Enix’s book on Matz. Other methods have employed similar concepts, but he was the first to deal with training a young cellist in such a way as to avoid injury (such as Focal Dystonia) through exercises based on a deep understanding of the anatomical/ physiological issues involved. At the same time, he is training the ear through the tonalities he uses, clefs, and the conceptual (as Starker makes reference to) such as the “geography” of the fingerboard. In tandem with the Etudes, he published pieces that use the recently learned (via the Etudes) techniques in a musical setting, sometimes in ensemble works for multiple cellos. In this regard, there is an inimitable relationship of technique to music. They are always intricately (but subtly) related. I suggest the 54 Etudes for young hands and 25 Etudes (lower positions) in particular.

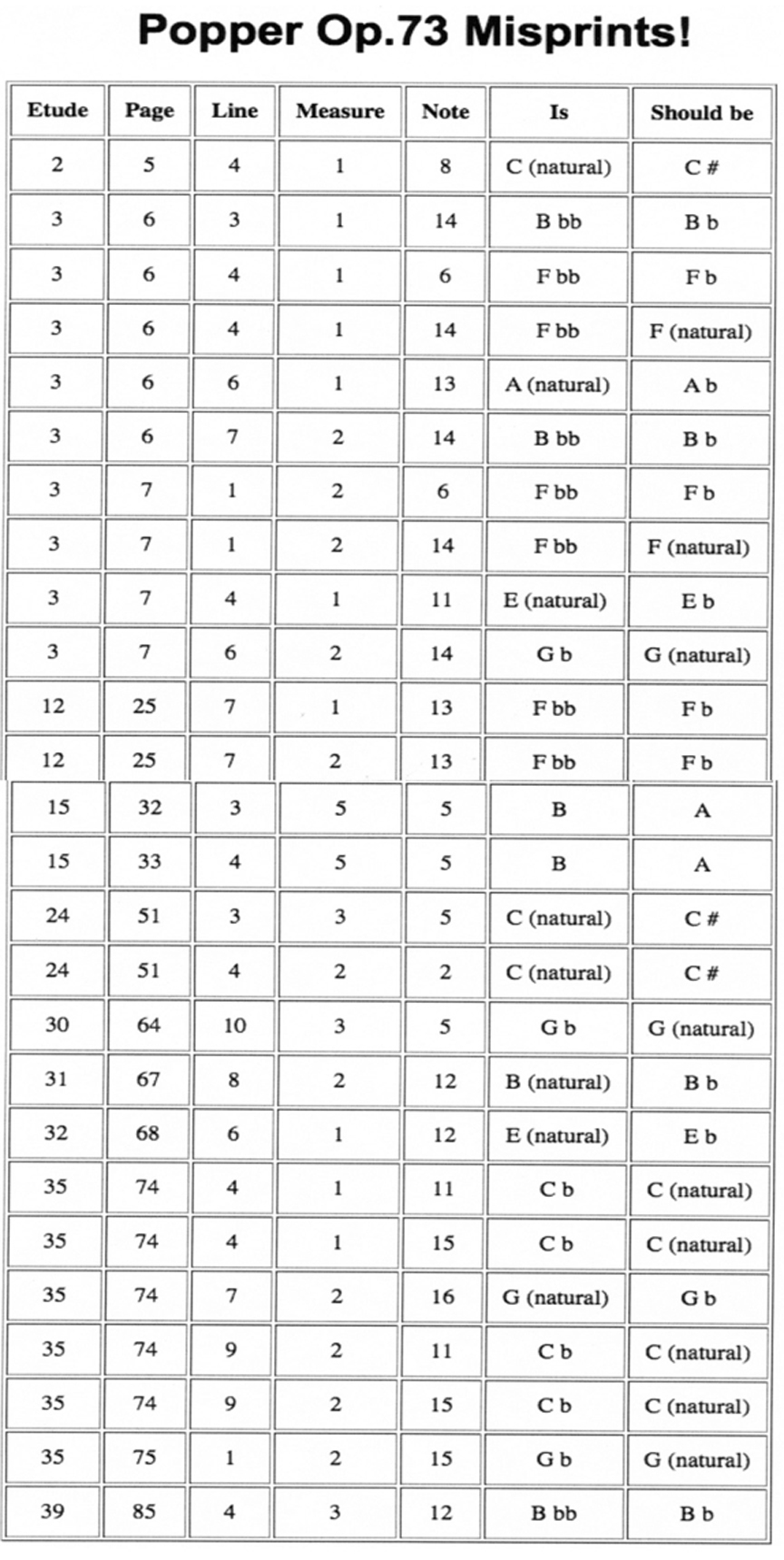

Recently, I got out the cello after a couple weeks neglect and decided to go through some of these etudes. All I can say is wow, what great materials! Musically simple, pleasant, and succinct, they are so well considered in terms of developing technique, at least as far as I have gotten in them, including those concerned with the introduction of thumb position. There are a few small errors (missing accidentals), but they are just tremendous for what they seek to do.

I can understand why Janigro, Silva, Starker, and Rose (among others) considered him to be the greatest theoretician of the cello. It is terrible that these works are not more widely available and used. Really just fantastic tools.

https://www.facebook.com/Stac3yK/posts/10103295602059101

https://archive.org/details/Matz_CompleteCellist/mode/2up?ui=embed&view=theater

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/184868530

The following is a copy of Luigi Silva’s proposed Treatise, also available (along with many other collections of well-known cellists’ papers) from the UNCG archives.

There is pressure THROUGH the thumb, not FROM the thumb. As you rotate the forearm and hand counterclockwise (pronation), the index finger naturally applies pressure down as the thumb applies pressure upwards. This does not come from squeezing, this comes from rotation, and it is applying the weight of the arm into the string. My thumb is flexible, but from a position of being slightly bent. While there are many small variations as to how to hold the bow, the basic principles of leverage and flexibility are common to all effective bow holds.

The Thumb and forefinger create a class 3 lever system, which allows us to apply the weight of the arm into the string.

A class 3 lever system:

object (string) force (index finger) fulcrum (thumb)

I use a hold that I learned from Antonio Janigro, and which was also used by Rostropovich, and occasionally by Harvey Shapiro and Lynne Harrell. Due to its location on the frog, it expands the size of the fulcrum, which increases leverage, and it puts the thumb against a smoother and more comfortable area of the frog than many cellists utilize.

While I like this very much, and find it very comfortable, it really isn’t different as to how it functions from a traditionally taught hold, as you move from the frog towards the tip, the right elbow rises and the forearm rotates, causing the hand to pronate. This pronation in turn focusses the weight of the arm/hand/bow into the string via leverage. What the hold pictured above does accomplish is that it increases the potential leverage by increasing the area over which the hand rotates by @21%.

top picture is of a “typical” bow hold

Bottom picture is the one I use.

Both photos were taken with the camera mounted in exactly the same position and the bow held in a fixed position (exactly the same)

In measuring the two circles in the pictures above, I found that the top example of a typically placed thumb created a circle with a circumference of 3 3/16 inches, and the second (alternative) placement created one of 3 14/16 (these measurements are relative to the scaling of the photos, not an absolute measure, but accurate for comparison). This is an increase of 21.4%. If one applies the same degree of rotation to each example, as one does approaching the upper part of the bow, the hold in the bottom photo creates more leverage, a greater application of arm/hand/bow weight into the string in the upper part of the bow.

There is no avoiding the bow change, only minimizing the effect of it in sound. The elements we have with which to address the change of bow direction are bow speed, pressure on the string (weight), angle of the bow in relation to the bridge and the string, and proximity to the bridge/fingerboard. Of these characteristics of bow usage, the first 3 are most relevant to the bow change. The “whipping wrist and fingers” that many teach has the tendency to speed up the bow and change the relationship of the bow/string angle in less than expert hands. If this is done with perfect control of the release of pressure it can work. But in my 50 years of observation, it is often not well done and often makes things worse. Of course, in the hands of a brilliant musician like Leonard Rose, this is extremely effective. Sadly, few of us are so extraordinarily gifted.

In my opinion, the less unnecessary motion of the fingers, wrist, and arm at the bow change, the better the outcome for most people. Lightening up the pressure/weight around the instant of the bow change and flexibility of the joints is a useful in this regard. There will always be some reaction of the fingers and wrist, but if this does not interrupt the plane of travel of the bow, the bow angle, etc., it is not a problem.

I was at a violin masterclass with Broadus Earle many years ago when he addressed bow changes. He made the point that even light shined on a mirror stops for a minuscule amount of time as it changes direction. Can we see that? No. How does that relate to the bow change? Like light on the mirror, the bow must stop as it changes. We cannot alter that fact, but we can train ourselves to have maximum control of the elements of bowing to minimize this. I have seen many approaches that suggest different motions at the point of change (circles, figure 8s, “shock absorber,” flipping the wrist), which when executed by great players (like Rose, for instance) are impeccable. Unfortunately, most people when doing these things cannot do them well- most of us are not Leonard Rose. The problem seems to me is that in many cases this extra motion causes a change in bow speed, the plane of the bow, pressure and/or direction that actually increases the sound of the change. Practicing slow scales with a drone string can help with bow control. When you play 2 strings simultaneously, the plane of the bow must be consistent, and when done with a metronome, the speed can be observed by comparing bow distribution relative to the beats; this is fundamental to consistent control of the bow, whether you are concerned with bow changes, or shaping a phrase. Once you can play with absolute control of the speed, pressure, and the plane of the bow, you can then vary those elements with greater mastery and more sophisticated musicianship.

You need to be able to sense the string surface and the way it resists moving with your fingers through the bow. Janigro made a particular point of this, too. Some people will say “carve” the sound, and if you really know how to use a knife when cooking, that is a useful image.

Orlando Cole and Lynn Harrell

Piatigorsky

(up- and down-bow staccato)

The Swan

Allegro Appasionata

Feuermann

Dvorak Rondo, Popper Spinning Song

David Finckel on bow strokes

Martele

Colle

Spiccato

Spiccato with Colle

Sautille

Overlapping Spiccato and Sautille

Colin Carr on bowing

The music for cello is commonly written in three clefs, bass (or F clef), tenor (or C clef), and treble (or G clef). When we first begin the cello, our music is in bass clef, as it neatly contains all of the notes in first position. As we develop, we begin to play a larger range of pitches, and the notes begin to go above the top notes of the bass clef. Composers use these other clefs in order to avoid lots of additional lines above the five lines of the staff (leger lines) that would be required in order to stay in the bass clef. This makes reading music easier, once you are familiar with these clefs. Then there is the “false” treble clef…

Bass Clef

Bass clef is known as F clef because the two dots to the right outline the note F. In bass clef, Middle C is on leger line above the staff. Bass clef is used for the lower register of the instrument, and this is similar to the bass human voice. The lowest note on the cello is the open C string, and that is noted two leger lines below the staff, and the bass clef is commonly used to notate from low C up to G above middle C, which is three leger lines above the staff.

Tenor Clef

The tenor clef is known as a C clef because the center of the clef is on the note middle C. In bass clef, this note is one leger line above the staff, and in treble clef it is one line below the top line of the staff. Tenor clef makes it easier to notate the cello’s mid-high range without a lot of leger lines. The notes in tenor clef are written a fifth lower than they appear in the bass clef. My first cello teacher introduced it to me in this way: imagine your A string is broken and you have to play everything on the D string (only it’s really your A string). You can try playing beginner level music that you already have which should be on the A string up to F above middle C. Play it on the D string. This will give you a mental image of the fingerboard for tenor clef, as the difference is a fifth, the same interval we tune our strings to. So when you see that F 2 lines above bass clef and you play it on the D string, it is right next to the C that is 2 lines above Tenor clef, so the notes look the same and relate to the notes around them the same way, you are just playing them a little further to the left.

Treble Clef

As mentioned before, middle C is one leger above the bass clef staff, but that note is one leger line below the the staff in treble clef, and it is used when we are required to play in the instrument’s highest registers. It is called the G clef because the circular part of the shape of the clef surrounds the line where G is written within the staff (the second line up from the bottom of the staff).

“False” Treble Clef

Certain publishers of the nineteenth century used the “false treble” clef, where the treble clef is notated an octave higher than it is played. I was involved in a conversation amongst music engravers regarding it the the other day, and it turns out that there is a specific convention using treble clef for cello during this era amongst publishers (almost all German). If the treble was employed in the context of a passage that also used tenor clef, it was to be played as written, if it was isolated (not in the context of a passage with tenor clef), then the “octave lower than written” applies. I’m sure it was a convenience to whoever was writing down music, but I hate it…

Intonation is about math. Many people feel that it can be “expressive” in that a solo line can be inflected subtly to exaggerate harmonic gravity The sense of a note “pulling” towards another, but in ensembles in most western classical music, it is all about the math of sum and difference tones. For me, this would include playing solo, as our instruments have natural resonances that can be enhanced by intonation that exploits it. Intonation is dependent on which combination of notes is played, because the pleasing set of combined tones (not just the notes played but their interactions) is what we like. Exploiting it can also increase resonance and projection.

Sum and difference frequencies:

When you play a note, you are shortening the string. This is due to the physics of a string, the lower the note, the longer the string, the higher the note, the shorter the string. It is not linear. A piano has the strings set to particular pitches and you push buttons that are equally sized and spaced apart. If you look at the frets on a guitar, you can see that they are closer together the higher the pitches are.

If you feel that you are uncertain where notes are, you need to spend time with scales, slow scales, so you can really pay attention to what is going on with your body and the instrument. Eventually your mental map of the fingerboard improves. It can be very helpful to play drone open strings with your slow scale work, ie, when you finger notes on the C string, play them together with the open G, when you play on the G string-open D, when you play on the D string, open A, and when you play of the A string, play open D. Of course, the sum and difference tones will be somewhat distorted depending on what combinations you are playing, but it is a reasonable way to work on the mental map.

Learning the notes, as Starker often remarked, is a matter of learning the map of the fingerboard. By this he meant a mental map of the fingerboard. Once you understand a position, it is mapped in your mind. I don’t think this is especially visual, as you need to understand how intervals relate to one another in a position. This is especially true in thumb position. Once you understand the tonal relationships accessible within a position, training the balance of the hand to maximize that access and minimize tension is feasible. So it really comes down to a combination of mental mapping of the fingerboard and training the ear to accurately hear the pitch.

I would add that there are no muscles in the fingers, they are controlled entirely by long tendons that are attached to muscles that are attached at the elbow. To maintain the position of the hand in the “holding an apple” metaphor takes a small amount of strength, and it should feel reasonably relaxed to do so. if the position of the hand and fingers is good, then a slight rotation of the forearm accomplishes most of what is required to put the fingers down and pick them up, a small flick of the tendons and it is complete. Squeezing and putting fully down more fingers than the finger required for the current note only adds tension and compromises control. It takes a good deal of time to master these things with consistency, so be patient. Scales are an excellent way to build this, as there is little to distract one’s focus from the technique.

When the arm approaches the neck at the correct angle to use rotation/leverage of the forearm to shift the weight of the arm and hand into the finger that is playing, it takes very little pressure to stop the string. The wrist should always be in neutral position, which lowers tension on the tendons that control the fingers where they pass through the wrist. The base knuckles of the hand should be arched such that the palm and thumb do not collapse. look at the 2 minute mark in the video below (which is about bow technique, but you will see how the fingers should work best in upper positions)

neutral position of wrist

There are a number of factors that effect the placement of fingers for intonation. The typical height of the A string above the end of the fingerboard is 4-5.5mm, and the C is 7-8.5mm. The higher the pitch of the string, the shorter its transit is, the lower the pitch, the greater its transit. Transit means the complete distance the string travels in a single cycle that produces its pitch. Because of the difference in transit, all of the strings are a different height above the fingerboard, which means that if you press them down to the fingerboard at exactly the same distance from the nut on the different strings, you will distort the pitch of the highest string less than the lowest string, meaning the fifths will be out of tune (the lower the string, the sharper it will be). In addition, each of your finger pads is a different shape and thickness, so this also influences what happens when you put your fingers down (especially if you are stopping a fifth with one finger). So many complications…

Many inexpensive instruments have necks (and more commonly fingerboards) that flex and twist as you play, which really makes intonation a moving target. This can be addressed, as if the fingerboard is not ebony, that can be changed, which will stiffen the neck, and some makers these days put a carbon fiber rod in the neck to stiffen it and add resonance.

There are strings that respond to changes in bow pressure and speed with changes in pitch more than others. In general, higher tension strings of smaller gauge resist this change in pitch much better that lower tension, thicker gauge strings do. They are also much more responsive to articulation. Refer to my post on strings for more information on this topic.

I have used a variety of tuner apps with different settings, and I think it is a mistake to obsess on the “cents” too much, a strobe setting is sometimes less disruptive. I usually tune the open A to the tuner, then tune the rest by ear (those sum and difference tones!). Some instruments seem more sensitive than others in that if you tune all the strings one by one, you might find that the bridge and tailpiece fluctuations that result from the string movements might alter the original A, so it might take a little time to get it all balanced.

Use weight/leverage more than muscle/tendon power to put fingers down. Remember, there are no muscles in the fingers, so the muscles that move your finger are in the arm near the elbow. If you use these too much, of course the hand is tense. If you press more than just the finger that is playing down, you are raising tension in the arm/hand/fingers and you are wasting the weight and leverage available. So, that’s what not to do and why.

So, what should you be doing instead? Think of the forearm, it has 2 bones in it. What does that mean for cello playing? It means that the forearm can rotate without any use of the upper arm or shoulder. When you play a note with the first finger, the forearm should rotate slightly clockwise (from the perspective of your elbow). This shifts the weight of the arm and hand toward the first finger. When you play a note with the 4th finger, you should rotate the hand somewhat counterclockwise, so that the weight of the arm goes into the 4th finger. Two things are accomplished by this, the motion of rotating the arm in the direction of the finger that will play releases the arm weight from the finger that was playing and shifts it to the finger that will be playing, and the motion itself moves the finger towards the string. As a result, more weight goes into the finger and the string (at the same time, tension is released from the other finger), and less effort is required to place the finger on the string.

Some cellists are unused to thinking about playing the cello this way, so you need to train yourself to accomplish this with slow, deliberate practice. Scale work is an excellent place to work on this, in addition to your practice of passagework. Another thing to bear in mind is that you do not need to press the string down into the fingerboard in order for the notes to sound clearly in most cases, especially the further you go from first position, as the string is most flexible in the middle.

Look at the video of Lynn Harrell in this link below. He is demonstrating spiccato, but he makes a point about the pressure required for the string to sound.

Fingerings

Generally speaking, we choose fingerings to make playing a passage as simple and efficient as possible. Most western music is about scale-like melodies or implied harmony (arpeggiation). Knowing the patterns of the scales and arpeggios goes a long way into being able to recognize these patterns in pieces that we play and finger them accordingly. However, there are many times when playing a passage on one string has a much more homogenous effect that is desirable. The choice then of when to shift is sometimes merely practical, sometimes entirely musical.

Playing fifths

There are a number of factors that effect the placement of fingers for playing fifths. The typical height of the A above the end of the fingerboard is 4.5-5.5mm, and the C is 7.5-8.5mm. The higher the pitch of the string, the shorter its transit is, the lower the pitch, the greater its transit. Transit means the complete distance the string travels in a single cycle that produces its pitch. Because of the difference in transit, all of the strings are a different height above the fingerboard, which means that if you press them down to the fingerboard at exactly the same distance from the nut on the different strings, you will distort the pitch of the highest string less than the lowest string, meaning the fifths will be out of tune if they are exactly parallel (the lower the string, the sharper it will be). In addition, each of your finger pads is a different shape and thickness, so this also influences what happens when you put your fingers down (especially if you are stopping a fifth with one finger). These things distort the relative location of the pitches, so it is never perfectly parallel from string to string.

Many cheap cellos also have necks/fingerboards that are too soft, which means the neck is unstable, making any double-stops unreliable. You need to experiment with these parameters in mind to find a solution that works for a particular passage.

More shifting

We shift from position to position, not finger to finger. It takes time to develop reliable muscle memory and to build an effective mental map of the fingerboard. Conceptualizing the positions is very important. Timing of shifts and understanding the mechanics of shifting are important, and many great teachers have suggested that introducing the upper positions early is important.

Scales and Arpeggios

The best thing about scales and arpeggios is that they give you the opportunity to focus entirely on technical matters without “musical” considerations. Memorization, phrasing, analysis, etc. are not relevant. Arpeggios are all about learning the topography of the fingerboard, in every key. You have to cover a lot of territory, so how you shift (early and slow motion, no matter the tempo) is everything (ditto bow control of string crossings). You must train your concentration to control your body accurately in space and time, if your mind wanders, that tells you that you are not working on this correctly. When you are in performance, how well you have trained this mind/body connection is what is going to give you success, so you really must consider how you approach technical practice. Arpeggios are prominent features in standard concerto repertoire (Haydn D, Schumann, Brahms Double) and standard orchestral repertoire (Wagner, Strauss). This will matter a lot, if you work on it properly.

Coordination in Fast Repetitive Bowing Patterns

http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0106615

Interview with Dr. Erwin Schoonerwaldt, Institute of Music Physiology and Musicians’ Medicine

http://stringvisions.ovationpress.com/2014/05/exclusive-interview-erwin-schoonderwaldt-part-1/

Motion Capture Studies in Music

http://stringvisions.ovationpress.com/2014/09/classical-mocap-part-1/

Dr. Schoonderwaldt’s motion studies of violin

https://www.youtube.com/user/schoondw

The middle finger offers much better flexibility for playing most pizzicato. Remember that the string works best when pulled side to side (like the bow does) and not up and down (unless you are supposed to make a “Bartok pizz” -type sound). Having your right hand supinated (rotated clockwise) gives you the most natural approach as the finger is designed to move most easily in this direction (up and down- like playing the piano, but side to side when rotated). This also allows you to hold the bow securely (but easily) with the other fingers while playing pizz.

Do NOT play near the bridge, the string is least flexible and responsive there, and it sounds ugly. The most flexibility of the string is at the midpoint, but that point changes depending on where your left fingers are on the string. For this reason, the easiest place is a few inches up the fingerboard with your thumb touching the side of the fingerboard for stability. Look for videos of jazz bass players like Ray Brown, they are the best models to emulate for pizz for cellists.

An important consideration is the regular practice of pizz so that our right hand fingertips and thumb are able to pizz without discomfort. It takes a while to build up the calluses that protect our skin from the friction endemic to playing pizz. When I was playing in a piano trio for many years, anytime we would program the Shostakovich Piano Trio in E minor, I would practice playing fortissimo 4 note chords with the thumb daily for weeks in advance, otherwise I could not perform this work without great pain. There are many pieces in the larger repertoire for cello for which we must be prepared to play pizz without pain.

One must find a way to prioritize practice time, and be very efficient with its use. Make that time your first priority and everything else fits around it. Every time you practice, you should have a specific goal in mind, and focus on that until you have achieved it.

Playing through a piece is not practicing. At the same time, it is wasteful to stop every time there is a problem. The most efficient way to practice is to divide up the piece you are working on into sections. The most productive goals to maintain are those you establish when you sit down to practice, every time. You should never play anything in practice without a specific goal. With each repetition, you need a specific purpose, indeed, you should not repeat anything without one.

Work with a metronome. As you work through a section, remember what issues you had the first time you went through it. Stop and consider what happened and what you need to do to correct it. If you cannot fix it the second time, slow the tempo down. If you still can’t fix it at the slower tempo, isolate each problem and slow it down further. Once you have solved a problem and can play it correctly 3 times in a row, then expand the isolated section back to the full section in the same tempo. Play it right 3 times in a row and then speed the tempo up. When you have the section in good shape at the tempo you want to achieve that day, move on to the next section. Make notes of the tempos you achieve each day and start the next session a couple of tempo markings slower than you reached the time before and proceed as before.

Longer term goals and timelines tend to be somewhat squishy, they are nice to have, but the timeframe often needs adjustment, either you meet the goal earlier than expected, or for various reasons, it takes longer than assumed. Say you have a recital/audition/competition scheduled, and that is a goal. Preparing for it takes planning and strategy to achieve a successful outcome. Aside from such goals, from week to week, you just want to get better. If you never play anything in practice without a specific goal in mind, every week you will be better. Goals achieved!

Recent brain research indicates that the most productive learning takes place if you stop your activity (in this case, practicing) after 25 minutes and take a five minute break. The brain can effectively process and store information best in this size segment. So, set a timer for your practice, set your goal for that time, get to work, and when the timer goes off, set it for 5 minutes. I started doing this after reading a couple of pieces on the research, and it really seems to work. It is also good for your body to break up the work this way, especially if you go back and work on something with a different set of physical challenges for the next segment.

tips for learning From the New York Times:

The studio for what is arguably the world’s most successful online course is tucked into a corner of Barb and Phil Oakley’s basement, a converted TV room that smells faintly of cat urine. (At the end of every video session, the Oakleys pin up the green fabric that serves as the backdrop so Fluffy doesn’t ruin it.)

This is where they put together “Learning How to Learn,” taken by more than 1.8 million students from 200 countries, the most ever on Coursera. The course provides practical advice on tackling daunting subjects and on beating procrastination, and the lessons engagingly blend neuroscience and common sense.

Dr. Oakley, an engineering professor at Oakland University in Rochester, Mich., created the class with Terrence Sejnowski, a neuroscientist at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, and with the University of California, San Diego.

Prestigious universities have spent millions and employ hundreds of professionally trained videographers, editors and producers to create their massive open online courses, known as MOOCs. The Oakleys put together their studio with equipment that cost $5,000. They figured out what to buy by Googling “how to set up a green screen studio” and “how to set up studio lighting.” Mr. Oakley runs the camera and teleprompter. She does most of the editing. The course is free ($49 for a certificate of completion — Coursera won’t divulge how many finish).

“It’s actually not rocket science,” said Dr. Oakley — but she’s careful where she says that these days. When she spoke at Harvard in 2015, she said, “the hackles went up”; she crossed her arms sternly by way of grim illustration.

This is home-brew, not Harvard. And it has worked. Spectacularly. The Oakleys never could have predicted their success. Many of the early sessions had to be trashed. “I looked like a deer in the headlights,” Dr. Oakley said. She would flub her lines and moan, “I just can’t do this.” Her husband would say, “Come on. We’re going to have lunch, and we’re going to come right back to this.” But he confessed to having had doubts, too. “We were in the basement, worrying, ‘Is anybody even going to look at this?’”

Dr. Oakley is not the only person teaching students how to use tools drawn from neuroscience to enhance learning. But her popularity is a testament to her skill at presenting the material, and also to the course’s message of hope. Many of her online students are 25 to 44 years old, likely to be facing career changes in an unforgiving economy and seeking better ways to climb new learning curves.

Dr. Oakley’s lessons are rich in metaphor, which she knows helps get complex ideas across. The practice is rooted in the theory of neural reuse, which states that metaphors use the same neural circuits in the brain as the underlying concept does, so the metaphor brings difficult concepts “more rapidly on board,” as she puts it.

She illustrates her concepts with goofy animations: There are surfing zombies, metabolic vampires and an “octopus of attention.” Hammy editing tricks may have Dr. Oakley moving out of the frame to the right and popping up on the left, or cringing away from an animated, disembodied head that she has put on the screen to discuss a property of the brain.

Sitting in the Oakleys’ comfortable living room, with its solid Mission furniture and mementos of their world travels, Dr. Oakley said she believes that just about anyone can train himself to learn. “Students may look at math, for example, and say, ‘I can’t figure this out — it must mean I’m really stupid!’ They don’t know how their brain works.”

Her own feelings of inadequacy give her empathy for students who feel hopeless. “I know the hiccups and the troubles people have when they’re trying to learn something.” After all, she was her own lab rat. “I rewired my brain,” she said, “and it wasn’t easy.”

As a youngster, she was not a diligent student. “I flunked my way through elementary, middle school and high school math and science,” she said. She joined the Army out of high school to help pay for college and received extensive training in Russian at the Defense Language Institute. Once out, she realized she would have a better career path with a technical degree (specifically, electrical engineering), and set out to tackle math and science, training herself to grind through technical subjects with many of the techniques of practice and repetition that she had used to let Russian vocabulary and declension soak in.

Along the way, she met Philip Oakley — in, of all places, Antarctica. It was 1983, and she was working as a radio operator at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. (She has also worked as a translator on a Russian trawler. She’s been around.) Mr. Oakley managed the garage at the station, keeping machinery working under some of the planet’s most punishing conditions.

She had noticed him largely because, unlike so many men at the lonely pole, he hadn’t made any moves on her. “You can be ugly as a toad out there and you are the most popular girl,” she said. She found him “comfortably confident.” After he left a party without even saying hello, she told a friend she’d like to get to know him better. The next day, he was waiting for her at breakfast with a big smile on his face. Three weeks later, on New Year’s Eve, he walked her over to the true South Pole and proposed at the stroke of midnight. A few weeks after that, they were “off the ice” in New Zealand and got married.

Dr. Oakley recounts her journey in both of her best-selling books: “A Mind for Numbers: How to Excel at Math and Science (Even if You Flunked Algebra)” and, out this past spring, “Mindshift: Break Through Obstacles to Learning and Discover Your Hidden Potential.” The new book is about learning new skills, with a focus on career switchers. And yes, she has a MOOC for that, too.

Dr. Oakley is already planning her next book, another guide to learning how to learn but aimed at 10- to 13-year-olds. She wants to tell them, “Even if you are not a superstar learner, here’s how to see the great aspects of what you do have.” She would like to see learning clubs in school to help young people develop the skills they need. “We have chess clubs, we have art clubs,” she said. “We don’t have learning clubs. I just think that teaching kids how to learn is one of the greatest things we can possibly do.

FOCUS/DON’T The brain has two modes of thinking that Dr. Oakley simplifies as “focused,” in which learners concentrate on the material, and “diffuse,” a neural resting state in which consolidation occurs — that is, the new information can settle into the brain. (Cognitive scientists talk about task-positive networks and default-mode networks, respectively, in describing the two states.) In diffuse mode, connections between bits of information, and unexpected insights, can occur. That’s why it’s helpful to take a brief break after a burst of focused work.

TAKE A BREAK To accomplish those periods of focused and diffuse-mode thinking, Dr. Oakley recommends what is known as the Pomodoro Technique, developed by one Francesco Cirillo. Set a kitchen timer for a 25-minute stretch of focused work, followed by a brief reward, which includes a break for diffuse reflection. (“Pomodoro” is Italian for tomato — some timers look like tomatoes.) The reward — listening to a song, taking a walk, anything to enter a relaxed state — takes your mind off the task at hand. Precisely because you’re not thinking about the task, the brain can subconsciously consolidate the new knowledge. Dr. Oakley compares this process to “a librarian filing books away on shelves for later retrieval.”

As a bonus, the ritual of setting the timer can also help overcome procrastination. Dr. Oakley teaches that even thinking about doing things we dislike activates the pain centers of the brain. The Pomodoro Technique, she said, “helps the mind slip into focus and begin work without thinking about the work.”

“Virtually anyone can focus for 25 minutes, and the more you practice, the easier it gets.”

PRACTICE

“Chunking” is the process of creating a neural pattern that can be reactivated when needed. It might be an equation or a phrase in French or a guitar chord. Research shows that having a mental library of well-practiced neural chunks is necessary for developing expertise.

Practice brings procedural fluency, says Dr. Oakley, who compares the process to backing up a car. “When you first are learning to back up, your working memory is overwhelmed with input.” In time, “you don’t even need to think more than ‘Hey, back up,’ ” and the mind is free to think about other things.

Chunks build on chunks, and, she says, the neural network built upon that knowledge grows bigger. “You remember longer bits of music, for example, or more complex phrases in French.” Mastering low-level math concepts allows tackling more complex mental acrobatics. “You can easily bring them to mind even while your active focus is grappling with newer, more difficult information.”

KNOW THYSELF Dr. Oakley urges her students to understand that people learn in different ways. Those who have “racecar brains” snap up information; those with “hiker brains” take longer to assimilate information but, like a hiker, perceive more details along the way. Recognizing the advantages and disadvantages, she says, is the first step in learning how to approach unfamiliar material.

six principles of good practice

http://www.violinist.com/blog/brucevln/201611/20852/

Dorothy Delay’s practicing mind map

http://travismaril.squarespace.com/blog/2012/2/5/musings-on-dorothy-delays-practicing-mind-map.html

Her lesson chart:

Her lessons were usually on a particular work or piece. She wrote the date by hand in the upper right hand corner. There are seven columns and 23 rows. Columns 1 and 2 have no heading. Column 1 is the list. The others are all blank. She filled in the month/day in the boxes where the criteria were met and put an x in boxes for what was discussed in the lesson. Columns 3 – 7 are headed with roman numerals for movements of the work. The 23 rows are separated by a double line in four sub rows with four groups of criteria. First group: 1. Notes, 2. Rhythms, 3. Fingerings, 4. Bowings, 5. Memory, 6. Intonation. Second group: 1. History, 2. Score, 3. Structure/Character, 4. Dynamics/Balance, 5. Pacing/Ensemble. Third: 1. Strokes, 2. Vibrato, 3. Shifting, 4. Articulation, 5. Coordination, 6. Violin Sound. Fourth: 1. Stance, 2. Violin position, 3. Bow Grip and Arm, 4. Left Hand position, 5. Head, 6. Face and Breathing

Heifetz on practicing

Shifting is the term we use to name the process of moving the left hand from one position on the cello to another position. Looking at the fingerboard provides neither clue or guidance. When people are performing, they may not wish to look at the audience because it is distracting or makes them nervous, so I would never presume they look in the direction of the fingerboard because they need to see their shifts. If they had to look in order to shift, they probably wouldn’t be on stage…

Shifting is about timing and balance. When we play a note, the weight of the arm should be balanced so that the forearm rotates slightly in the direction of the finger that is playing, and simultaneously the elbow must be at an angle such that this is possible. This allows the weight of the arm and hand to be applied effectively on the finger that is playing. When shifting to higher positions on any string, you must raise the elbow slightly in anticipation of the new position, as the shape of the cello requires this once we approach the body of the instrument. Once the elbow is in position for the new position, it is simply a matter of opening the elbow a bit to move the hand into the new position. Anticipation by definition means that these things take place before the change in position. To fully anticipate an upward shift, imagine first that the note preceding the new position is divided in half (in your mind). As you begin the note before the shift begins, raise the elbow to the plane it needs to be on in the new position (this releases some tension in the hand and weight from the finger). Halfway through the note before the new position, begin to move the hand at such a speed that the hand arrives at the new note in time for the new note to sound. This needs to be practiced very slowly with a metronome until the brain understands the timing, and the body is well coordinated. If you want to hear the shift, you keep the bow at the same speed and pressure throughout the shift (it is useful to do this until you have the timing and the coordination well trained), and if you do not want to hear the shift, you release the pressure of the bow and slow it down during the shift. Varying this combination of speed and pressure with the bow is how we make variety in our shifts. Once mastered, there are variations in this (such as the delayed shift, where the slide happens at the time the new note is to sound and the new note is slightly delayed as a result. A great pianist will play a melodic note slightly late to everything else as a way to make an espressivo accent. We, of course, can make an espressivo accent by shaping a note with the bow, but I hope you understand how the delayed shift and this piano technique have similar expressive purposes. A good way to practice shifting is to play very slow scales with a metronome set for 2 beats for each note you play (that way the timing of the shift can be disciplined).

Letting go of fear important; shifting is like walking, it is all about balance and pacing. We all can walk (absent disability), and we can all shift with ease, so there is no cause for trepidation.

Many of the great teachers (Rose, Starker, Parisot, Janigro, etc.) distill the principles of playing down to a very basic level. Whether your hand is small or large isn’t relevant, really; the balance of the weight of the arm as applied through the discrete rotation of the forearm, in both the left hand and the right (with somewhat different involvement of the muscles of the back regarding each). For the left hand, rotation equals release of the initial finger’s “pressure” and the application of it to the new finger, the weight of the arm/hand being equal upon each finger in its turn. In the case where the hand is small, rotating the hand reduces the “stretch” in melodic (non-double-stopped) intervals, just as it does for a larger hand, the difference being the amount of rotation and the anticipated distance between the fingers that is required. Moving from one position to another is also a matter of anticipation (minimizing motions that occur during the movement of the hand from one position to another by creating the new position as much as possible in anticipation of the shift). The balance of the hand in the position before the upward shift (typically favoring either the 4th or 3rd finger) is different than that after the shift (typically the 1st finger). Starker and Parisot taught/teach a clockwise-circular motion of the left elbow in anticipation of the shift, which naturally shifts the balance of the hand. I personally feel that this is a good way to get the concept of shifting balance well understood, but it is important that one not introduce too much extraneous motion into the shifting process itself once understood and accomplished, as less extraneous motion equals less likelihood of error.

In general, the downward shift utilizes all of these same considerations, anticipation and the attention to the change of balance of the hand for the two different locations.

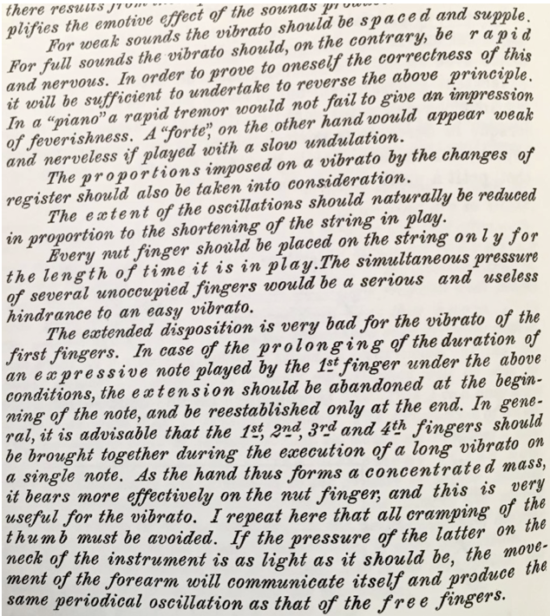

Vibrato comes from the elbow, whether it is called arm, wrist, or finger vibrato. These are misleading terms, as people tend to think that they refer to where the vibrato originates. They do not; what the second and third terms mean is that the joint being referred to takes a greater degree of flexibility when employed, producing a varied speed and amplitude particular to that joint’s flexibility. I have seen people demonstrate “wrist vibrato” that was nothing more than the rotation of the 2 bones of the forearm coming from the elbow. Bernard Greenhouse would occasionally employ something close to a true wrist vibrato (moving the hand from the wrist joint) but he employed this very infrequently, only on certain notes of a phrase, and only in lower positions. A very particular color of sound, and not how he normally employed vibrato.

Many other fine cellists sometimes play with the thumb released from the neck, and it is not at all controversial (though some pedants may say so). Look at videos of any cellist whose sound you are fond of. Chances are good that they will release the thumb at least occasionally. The thumb has nothing to do with the vibrato, and it is, if anything, usually the source of trouble when someone has a problem with vibrato.

Vibrato is only very rarely from the rotation of the hand, as the range of speed of oscillation in this manner is very limited. The most flexible vibrato originates from the forearm/elbow, which allows for the greatest range of speed of oscillation and greater ease of connection of the vibrato from note to note. Any forearm rotation that occurs should be incidental. It is always most efficient to use the largest possible muscle for the action at hand, as there is less energy and effort required to move a large muscle by a small amount than a small one a large amount, so by using the forearm to initiate the vibrato, this efficiency is possible. This concept of muscle use is an important aspect of Casal’s legacy.

In order to produce a “legato” vibrato, one that continues evenly from finger to finger without interruption when playing a melody, it is necessary to have a very consistent balance of the weight of the arm and hand regarding the finger that is playing. The thumb can be used as a pivot point, or can be released from the neck entirely as one gains greater mastery. Putting the fingers down is not just about using muscles to place the finger, it also includes a slight rotation of the forearm (and hand) so that the arm weight is balanced on the finger that is playing. To include vibrato with this action, one must first have consistent control of this balance. As vibrato is the linear action of the forearm that moves the finger pad down and up the string to change the pitch fractionally, it must be carefully coordinated with the action of placing the fingers. Ideally, the motion of vibrato is independent of that of placing (and displacing) of the fingers on the string such that it can be continued even while the fingers/notes change, creating a consistent quality of sound (and therefore easily varied) through any phrase as desired. The other benefit of this is a very relaxed and flexible left hand, as you cannot achieve this consistency with much tension in the hand.

As arm vibrato comes from the elbow, and pitch change on the cello is linear (following the line of the string), it is necessary that the act of vibrato is also linear. The motion of vibrato is not unlike shifting, in that the forearm moves the hand up or down the fingerboard parallel to the string to effect change in position/pitch. As vibrato is a subtle change in pitch, the motion is much smaller than when changing positions. The basic motion is a slight closing and opening of the elbow that allows for the fingerpad to move slightly on the string to alter the pitch. It is most often taught that the finger first establishes the pitch in its initial contact with the string and then descends and returns to the pitch. How wide the change in pitch is is determined by the amount of the fingerpad that comes in contact with the string. Some people have huge fingerpads (like Bernard Greenhouse or Lynn Harrell), so there is not a lot of motion required to accomplish this. Other people have considerably smaller fingerpads, which requires more considerable motion in order to create a similar amplitude. In general, having the hand at a slight angle, such that the base knuckle of the 4th finger is a bit further from the string than that of the first finger (this is as opposed to that school which suggests that the base knuckles be parallel to the string) is better. There are a number of reasons that for most people, the former is a superior approach, but I will not get into that here. As regards the angle of approach of the hand to the fingerboard and vibrato, having this angle in place makes a wider fingerpad contact with the string possible. You can start with the edge of the tip of the finger on the string and descend across the fingerpad at an angle across it, maximizing the area of contact and therefore the amplitude of the vibrato. To move the fingertip on the string, you need both the knuckles of the finger and the wrist to be flexible, as you pull and push the hand from the elbow (NOT the shoulder). This should be done very slowly and sound like a glissando, not 2 distinct pitches, top and bottom. It is a good idea to do this with a metronome to practice this in slow motion (not just slowly). Try the metronome set somewhere between 40-60 bpm and imagine that you are playing half note for the top and a half note for the bottom of the pitch. Bear in mind that you never sit on either the top or bottom pitches, you are always in motion. 4th position is a good place to begin. Remember, you are NOT rotating the forearm at all. You are pulling and pushing the fingertip down and up the fingerboard (“pumping” is how Paul Katz describes it in the video example below). Once you can do this easily on all 4 fingers, then make each pitch a quarter note, then 1/8th note, triplet 1/8ths, 1/16th notes, and setuplet 1/16th notes. There is an exercise in Diran Alexanian’s book (available at IMSLP.org) along these lines, though the explanation is not always the most clear. The thumb cannot be tense or stiff, indeed you can see that Yo-Yo Ma (and many other excellent cellists) often plays without his thumb. The thumb is at best a point of reference for the hand, there to guide the fingers and the rotation of the forearm that channels the weight of the arm into the fingers. Pressing with the thumb will only do harm to your playing and limit the freedom of motion of the vibrato

Diran Alexanian on vibrato

In learning to vibrate, it is useful to understand that the goal you are reaching for is a relaxed and balanced left hand, so that as you develop a vibrato motion, one must not lose sight of this.

Vibrato in slow motion (scroll down for the cello)

https://www.thestrad.com/6884.article

I have never seen a study such as this that any real scientist would look at and say that it proves something. From what I have seen, these are all flawed in their design. The current authors in question have published other such “studies” before, and while I am certain they are quite sincere in their intent, the results are problematic to me.

In this paper, the vast majority of the oscillation is below the pitch, and if you were to crunch the numbers of the frequencies for either mean or average frequency, it would be below the pitch center intended, not equally on both sides of the pitch which the authors seem to suggest. As to the cellist in this study, the pitch on every finger but the 4th is placed sharp of the intended pitch in the unvibrated note, but thereafter the range of frequencies within the vibrato has what appears to be the same pattern as the violinist. Because it starts sharp, it appears on the graph as being centered on the pitch. Again, if you were to crunch the numbers, it would have the same effect as with the violin, only it would be sharp to the intended pitch because it started out sharp. While this study intends to prove that vibrato is symmetrical around the intended pitch, it fails to accomplish its aim for these reasons.

In one of David Finckel’s videos on the topic, he slows down Fischer-Dieskau singing to study it for speed, width, and relation to pitch. Sounds pretty awful to me slowed down, kind of nauseating. I personally was more enraptured by his nuance (the variety of vibrato) and “musicality” than by his intonation or tone. I found it interesting that when Finckel demonstrates a vibrato in another of these videos equally on both sides of the note (below), he quickly adjusts his finger such that the top of the oscillation pitch goes down a fraction and THEN sounds in tune (at least to me). He makes the vibrato so that the top is only slightly above the pitch. This is consistent with the observations I made of the study above.

To me the controversy is not so much “is it only below the note,” or “equally on both sides of the pitch,” but where the actual pitch is within the oscillation. In this most recent illustration, it is clear that the vibrato is NOT equally on both sides of the note. I practice vibrato every day that I play as part of my warm up, and I focus it on below the note. However, as each person’s hand and finger shapes are different, and each finger does approach the string slightly differently, where the note starts is more dependent on that than anything else (rather than the vibrato’s focus). In my case, my 4th finger curves slightly back, compared to the others, so that when I place that finger on the string it is the upper part of the fingerpad that lands first and the vibrato goes down from there. It may well oscillate slightly above thereafter, but that is the initial action.

Here is a short discussion of vibrato with Paul Katz. He talks about Greenhouse’s approach, which I would amplify a bit. The “angled” approach allows the vibrato to be initiated from the elbow (no involvement of the shoulder whatsoever). Greenhouse used many variations on this gesture to color the sound with variety; more/less flexibility on the finger alters amplitude and speed, as does a more active wrist, etc.

Katz on Greenhouse and hand positions with vibrato:

Another aspect of vibrato involves sum and difference tone math, which accounts for why vibrato makes an instrument (or voice) sound louder. Yes, it’s true! Consider that in the later classical era, when concert halls became more common for the public performance of music (rather than in churches or the residences of nobility), vibrato became much more common because those making use of it were heard more easily. Those singers and string players who employed it projected better into the larger spaces of these new public arenas, and as a result, others soon adopted the practice. The reason that this is so is that the vibrato creates many more complex waveforms in the sound (more “sum and difference tones”) that literally make more sound, as well as more reflected sound (ambience) in the hall. In stringed instruments, this creation of more sound begins within the body of the instrument itself (more complex waveforms within the instrument) as well as how those more dense soundwaves fill the hall.

Weight training can hamper your playing. How? Two ways: poor form can cause injury to soft tissues, joints, neck, and spine. Training with heavy weight, even with perfect form, shortens the muscles (that is the principal manner in which they bulk up), which stretches the tendons on both ends of the muscle, putting them on a higher baseline of stress. Stressed tendons damage more easily, and as tendonitis is the most common injury among cellists, we need to engage in this activity with some caution.

Do I mean by this that you should not train with weights, absolutely not! The question becomes how should you train. You need to train so that your muscle system is balanced, as unbalanced structures are prone to injury. Weight lifting does not strengthen the muscles of the shoulder capsule (the 4 muscles of the rotator cuff) and building mass all around them makes them more vulnerable. Strengthening the rotator cuff is difficult to do because of its structure, and it really takes expertise that you won’t find in any gym to do this. Absent this expert guidance, the safest thing to do is use lower amounts of weight with higher repetition and great attention to both form and variety. Don’t rely on a gym rat trainer to give you help, most of them I see in gyms are not competent to protect you from injury. Their interest in too many cases is to bulk you up, which is not our best goal.

Here is a video from a doctor of physical therapy that details how the rotator works and gives lots of useful information how to incorporate this into workouts

There are many considerations in forming an interpretation of a piece of music, the era of its composition, attention to issues of historical style and practice, finding a reliable text to work from, issues of structure, harmony, and counterpoint, and more. But for me, two basic formal features of western classical music that seem too often to be neglected are how to present a coherent narrative for the listener in regard to repetition and development.

As material is repeated, there is the fact that as a repetition, it has two important characteristics for us to acknowledge: the first time you hear something, it is new, and we experience it in just that way, in its unfamiliarity. As it is repeated, it gains in familiarity, yet each repetition has a unique place within the music as it unfolds. As we perform these repeated passages, we have the opportunity to make them unique in a variety of ways. As much or our repertoire shares certain features that derive from nature, principally symmetry and asymmetry, we have the possibility of using these characteristics to both provide variation of expression and in doing so to move the narrative of the piece forward. For example, most phrases in Beethoven are asymmetrical. This makes it easily possible to inflect a repeated phrase differently, say by phrasing it dynamically up and down or down and up to subconsciously clarify its asymmetry for the listener. We can vary the stresses within the phrase. Think of any sentence you wish to speak and say it repeatedly with an accent on a different word each time. That is the idea. On the cello, we have several additional ways of coloring the sound, as well, bow speed and placement, speed and width of vibrato, for example. Below is a funny example of variety and repetition from the celebration of Shakespeare’s 400th birthday.

I was trained as a “modern” cellist, most of my career was on modern instruments with endpins and metal strings, always exploring any new developments in each, and more. But as a modern player, I also studied scores, searching for authoritative “urtext” editions, manuscripts, and first editions of the “standard” repertoire. The idea was to seek understanding of a composer’s intent, and exploring the context of the period in which they lived and worked. I was often frustrated with learning Bach’s Solo Suites, especially as I grew up playing in an orchestra that specialized in the Cantatas, and there just seemed so many discrepancies between this music, which had strong foundations in the original texts, and how the Suites appeared in print and was heard in performance.

As a result of this, for me, regarding Bach, the best editor is the one who does the least. Anything that is not in the manuscripts that exist is editorial. Do you want to learn Bach, or someone else’s opinion on what Bach intended? I believe that there is no real choice to a musician who wishes to seek a composer’s intent, you go with the least editing. You don’t seek to interpret an interpretation of an interpretation. That result seems to be more like the result of a game of “telephone.”

[The game of telephone: Players form a line or circle, and the first player comes up with a message and whispers it to the ear of the second person in the line. The second player repeats the message to the third player, and so on. When the last player is reached, they announce the message they just heard, to the entire group. Errors typically accumulate in the retellings, so the statement announced by the last player differs significantly from that of the first player, usually with amusing or humorous effect. It is often invoked as a metaphor for cumulative error, especially the inaccuracies as rumours or gossip spread, or, more generally, for the unreliability of typical human recollection.]

“On November 2016, Bärenreiter Verlag published Bach’s Cello Suites of “New Bach Edition, Revised Edition” (NBA rev. 4 / Editor: Andrew Talle).” This is the most recent edition, yet it contains some errors:

https://bachcellonotes.blogspot.fr/2017/02/new-bach-edition-revised-nba-rev-4_13.html

Here is a review of the new Barenreiter Bach Suites (2016). Barenreiter also publishes a synoptic edition the compares line by line the early manuscript copies and the first published edition.

https://www.baerenreiter.com/en/shop/product/details/BA5277/

There are many editions available here for free, including facsimile manuscripts

http://imslp.org/wiki/6_Cello_Suites,_BWV_1007-1012_(Bach,_Johann_Sebastian)

Of these, I prefer the Bach-Gesellschaft Ausgabe (edited by Alfred Dorffel), which was edited by a musicologist/organist, not a cellist. Why is that a good thing? Because decisions about slurs are about being consistent with the preponderance of the extant manuscripts, not someone’s bowing ideas. The parts are very clean (no fingerings). This is this best free download to start with, IMO. You can look at lots of options from the IMSLP list if you need fingerings and bowings, but they often have little to do with what Bach wrote.

Zander Masterclass

Whispelwey Masterclass

I think we must study Bach Choral works, arias from the cantatas (check the cello parts, Bernard Greenhouse played in the Bach Aria Group for years, after all), and the keyboard suites. Fingerings are not that big of a deal, look at the chords and scales and the fingering is usually pretty obvious. If they aren’t, then that is where to concentrate your initial efforts (scales and arpeggios, with a teacher, if possible, but there are many scale/arpeggio books available). Bowings in the Suites are problematic only in that there is no original manuscript from Bach’s own hand, only copies made by others. By looking at the works I suggest, you will see what common types of articulation patterns exist consistently in Bach’s writing for cello (like arpeggiated chords, commonly 3+1 or 1+3, etc., not as commonly 4 (or 8) to a bow as many “modern” editions contain, 2+1+1, et al), but modern cellists rarely seem to do this, even if it is in the existing manuscripts and the Gesellschaft, so any online “tutorial” is likely more of the same distorted stuff. Casals’ “revolution” was to program the Suites in performance (most uncommon at the time), and that you should study them and make them your own, not that you should play them as he himself did. That was Bernard Greenhouse’s experience gained from working with the great Catalan cellist.

By looking at the keyboard works, you see similar patterns of articulation. Bach most often played the keyboard, and I believe that his thinking on articulating in archetypal works like French dance suites (they are “types” by definition) is clear in these works. By listening to great keyboard players in this repertoire, you get a very different idea of tempo, pacing, and consistent articulation. Zander pretty much nails it, in that regard. The suggestions he makes are compelling.

These things are the very basis of what makes Bach’s music what it is: when harmonic rhythm changes, this needs to be clear, ditto a hemiola; how melodic material changes dependent on the chord it occurs within, and where the key changes take place tell us much about the journey we are on, and structurally, where we are within that journey. These are the indicators, the signposts and the scenery on our path, and we need to animate our understanding and our performance with them.

Robert Schumann wrote piano accompaniment to the suites, and it’s available at IMSLP. Antonio Janigro (who had been a student of Diran Alexanian, who published the first widely distributed edition of the Suites containing the Anna Magdalena manuscript facsimile) played the suites on the piano and played the Schumann arrangement from memory in class; very illuminating.

Among the best training for playing Bach is to play the continuo (and solo) parts of the Cantatas and Masses (particularly Arias and Recitatives), followed by the orchestral suites. You can get the music on imslp.org and play along with recordings to get a feel for it. This will give you the sense of the range of articulations (be mindful of the words in this regard!) in the vocal works, and the rhythmic inflection in the Dance movements of the orchestral suites. Then get a clean, un-bowed and un-fingered edition of the Suites and do your own hiking. It isn’t Mt. Everest, it’s the Appalachian Trail.

In the 1980s, my first former mother-in-law (at my suggestion) transcribed the 4th Suite for Harpsichord. I recently found a very old, not very high quality cassette tape (remember those?) of a performance. I attempted to make it reasonably listenable, and the result is linked below. I think it offers an excellent example for cellists to consider thinking about the Bach Suites not as cello pieces, but more as “pure” music.

https://www.jsbachcellosuites.com/baroquecello.html#UCxbg2sZ

I am aware of this place as a source for reasonably priced reproduction baroque instruments

https://lazarsearlymusic.com/collections/violin-family

Here is a fine maker of reproductions

https://www.gabrielasbaroque.com/cellos

Evolution of cello and bow. There are different conclusions from different sources:

baroque instrument set up, by a string maker

http://www.damianstrings.com/baroque%20set-up.htm

evolution of violin construction

http://www.kuijkenviolins.com/baclamo/index.html

history of the violin and its accessories

https://www.boisdharmonie.net/en/publications/history-of-music

Development of bowed stringed instruments

https://www.scribd.com/doc/316517255/Shapes-of-the-Baroque

the Baroque violin

http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1235&context=ppr

evolution of the violin from baroque to modern

http://www.roger-hargrave.de/PDF/Artikel/Strad/Artikel_2013_02_Evolutionary_Road.pdf

http://www.roger-hargrave.de/PDF/Artikel/Strad/Artikel_2013_03_Period_of_Adjustment.pdf

Beethoven’s five Sonatas for piano and cello offer a magnificent distillation of twenty years of development as a composer into two hours of listening. His mastery of the conventional musical forms and structures of the time was clear from his earliest published works, and that mastery made it possible for him to subvert the listeners’ expectations in ways that would create a radically new expression of emotion in music.

The “original instrument” and “period performance” movements of the second half of the twentieth century gave audiences and performers alike new insight into and experience of the sound of western classical music as it might have been performed historically. Despite those developments, the solemn ritual of modern concert life has little to do with the manner in which much of this music was presented when new. Small-scale chamber works were not often presented in grand concert halls, but were meant for performance in more intimate environs. The domestic nature of these events was well described by the violinist and composer Ludwig Spohr, and music was often one of many simultaneous entertainments. Conversation, food, wine, card games and music intermingled in the social fabric, and one was free to listen attentively or not, and there could be lively comments made to the players even as they performed.

It was for just such an occasion that the Opus 5 sonatas presented here were written. They were dedicated to King Friedrich Wilhelm II, a gifted amateur cellist for whom Haydn and Mozart composed string quartets with unusually prominent cello parts. These Sonatas served to introduce young Beethoven to Europe’s influential musical society. Beethoven performed these works with the great French cellist Jean-Louis Duport, the solo cellist of the King’s orchestra. In these two works, Beethoven establishes his mastery of the conventional forms even as he utterly defies their conventions. Most of the sonatas of Haydn and Mozart with which Beethoven’s audience would be familiar were cast in three or four movements, and were typically ten to fifteen minutes in length. Both of the Opus 5 Sonatas are twice that duration, and each consists of only two movements. Even more radical is that each begins with an extensive slow introduction, a feature usually employed by Haydn and Mozart in symphonic literature to signify a particularly serious work. More importantly, that attention is richly rewarded as these works unfold. In these two sonatas, dramatic contrasts of volume and mood, and of sound and silence in the introductions serve the purpose of demanding that the audience pay heed. Not a bad idea for a young composer looking to make his way in the world. The first sonata has another unusual characteristic that Beethoven develops further in his “late” works. Nineteen minutes into the first movement, the tempo changes abruptly three times within a few seconds, first with a sudden slow echo of the introduction, followed by eighteen extremely fast measures before returning to the original tempo. In the second movement, the tempo becomes much slower for just two measures, again echoing the introduction, just seconds before its conclusion. It is both radical and brilliant. In working on such a large canvas for his “domestic” works, Beethoven set the stage for the “heavenly lengths” of the works of later composers.

By the time he completed the Sonata in A major, twelve years after those of Opus 5, Beethoven was at the peak of his fame. The first four symphonies, nine of the string quartets, and four of the piano concertos were before the public, and his growing deafness had yet to keep him from performing. The A major sonata is both the most widely performed of these sonatas, and is, at least on the surface, more conventional than its predecessors. It is cast in three movements, but instead of the expected fast-slow-fast progression, its movements proceed as fast, faster, and fast again. The opening movement has a lyricism and generosity of spirit that is reminiscent of the first “Razumovsky” quartet or the later “Archduke” trio. The middle movement, called a scherzo, is not in the form conventionally associated with that term. In place of the clearly defined scherzo-trio-scherzo one might expect, he presents two alternating contrasting themes, the first of which features a melody that begins (and remains) on the “wrong” beat, while the second is more lyrical and more gracefully comported. The last movement is in “sonata” form rather than a rondo, and begins with a slow introduction that at first hearing could seem to be the slow movement one might have expected.