A Question Answered: Influences on a Life in Music

Influences on a Life in Music

A few years ago, Robert DeMaine, the principal cellist of the LA Philharmonic, posted a topic on the now defunct Internet Cello Society webpage asking people to reflect on people who were important in their lives. This was my reply:

This is going to be a long one, but I think most of us have long stories to tell of what took us on our journeys. As I have been struggling with some major health issues the last few months, the opportunity that Robert presented with this topic gave me the chance to breathe and reflect on my path.

My family had settled in Ft. Worth, Texas in the fall of 1962. The next fall, Kennedy was assassinated. Shock, grief everywhere. Then came the Beatles. Joy and excitement in something new and thrilling. I started guitar lessons with an itinerant guitar player who came to the house. Then a quartet played in our school encouraging 3rd graders to sign up for violin. I did. The fall of 1965, we rented a violin and and I started in Mrs Virginia Hansen’s class once a week, using the Samuel Applebaum (the Guarneri Quartet’s violist, Michael Tree’s father) books. I went through the 3 books she used for 4th, 5th, and 6th grades in 2 months on my own, then had to have my tonsils out. When I came back, she asked me if I would like to learn the cello, as her cello player was going to graduate. She said she could get me a cello and the books, but that she couldn’t teach me to play it. I said that was fine, because I’d “already finished the violin.” (!!!) That summer, I took a week long group class with Professor Harriet Woldt (TCU/ principal of FW Symphony) with a bunch of other new cellists. In the fall, I began lessons with her most advanced student, Ms Linda Ferguson. Progress was fairly rapid, as I took to it quite naturally, and she was a good and charming teacher with a rye sense of humor. Lessons were often in a room where the ancient instruments were kept, and she invited me to play them after we finished our hour. Krumhorns, Gambas, viols of other sizes, she showed me what the notations meant and where the notes were, and we would plow through music. I was too young and naive to understand that I should not be able to do it… Linda went on to graduate school in Michigan but fell on ice, injuring her back, and had to give up the cello. She became a musicologist and I heard that she ended up teaching at the Mozarteum in Salzburg.

At one point, she started me on the D minor Klengel Konzertstucke. I really liked it. The opportunity came up to audition for a Christmas break string program at Baylor, and I went. There, I was waiting in a hallway to play for the cellist on the faculty, Lev Aronson. I heard some guy screaming, “Beethoven was not some guy from Waxahachie!!!” I thought, hmmm. Then the kid before me came out a bit later in tears. Hmmm, again. I went in, and Aronson introduced himself (very elegantly attired, and with his complicated European manner), and asked what I would be playing. I told him the Klengel and he let out a little grunt and gestured to a chair. As I started to play, he began to weep, copiously. When I finished the exposition, I stopped, and he told me a story about when he went to audition for Klengel, with this piece. Later that afternoon, all of the cello students gathered in a larger room, and Lev entered with his Gofriller and viciously ripped into 4 octave scales with a massive sound. I was stunned and intrigued by this madman. He got me a scholarship for a summer program they had, and there I had more exposure to him and to other faculty. First time I played in a real orchestra (Beethoven!), and chamber music (piano trios, in what would set a precedent for my future career). Because of family issues, it was not possible for me to continue to work with Aronson (I had a brother with schizophrenia and mild retardation, as they described it at the time), so I continued to work with Ms Woldt.

Ms Woldt also taught theory, and was both very funny (a serious punster) and a very serious musician. Her husband had been a composition student of Hindemith’s at Yale, and later studied in Vienna, where he played French horn with the State Opera. I worked with both of them in my musical studies. They were a very unusual couple for that era, they adopted 4 kids that no one wanted, kids with problems. They were big supporters of liberal causes, American Civil Liberties, etc. They put their hearts where their beliefs were, no empty talk, action.

My sisters and my best friend at the time studied with the FW Symphony Concertmaster, Kenneth Schanewerk. Kenneth had studied with the founder of the FT Worth Symphony, Brooks Morris, and later with Roman Totenberg, and he became a very important mentor. He invited me to join the University Chamber Orchestra, though I was but 13 (and playing the cello for 2 years!). We played a lot of challenging repertoire, Stravinsky, etc. and I loved it. I joined the FW Youth Orchestra later that year, where the conductor was a brilliant young classical sax player named John Giordano. In 1969, the FWYO went on a 6 week tour of Europe. The culmination of that was a festival in St. Moritz, with an international orchestra composed of members of the various participating orchestras conducted by Stokowski. Our orchestra played a program of contemporary works by local composers, including a massive aleatoric work featuring electronic music from the synthesizer studio at what is now UTNT. It was a big hit. All this while my friends back in Texas were going to the rock festivals of that Woodstock Summer and doing Acid…

Many of my friends were starting bands in those days, and I would get together with them and listen to all kinds of music, jazz, blues, English prog, Hendrix; I brought Stockhausen, Berg, Stravinsky, Debussy… Then we started to jam. We formed a band that became well known in area bars as “Master Cylinder.” Most of the guys were older and in the jazz program and electronic music program at UTNT. Started playing in bars at 15. Met lots of girls, older girls with their own apartments. At TCU, there was a very active piano department where Lili Kraus was encamped with a group of marvelous young faculty around her. As the string department was not large, I got to coach chamber music with her several times. A true force of nature, passionate and heedless of convention. That summer, I went with my best friend to Taos, where Schanewerk had founded the Taos School of Chamber Music years before with Chilton Anderson (an amateur cellist, rancher, and heir to the Eastman Kodak fortune). Kenneth had a wonderful house there on the rim of a canyon that he had built himself. Not the canyon, the house. We went up to work on people’s houses, fixing cracks in the adobe that formed over the winter, and spreading fresh tar on the roofs. We stayed with Kenneth part of the time and camped out part of the time. Lots of chamber music, lots of adventures. I played for Robert Marsh, who was on the faculty at the Taos School at the time and got a scholarship for the following summer there. Went to a party at Georgia O’Keefe’s. This was the summer when all of the folks who burned out in Haight-Asbury formed a commune outside of Taos. It was a different world than we inhabit these days.

Back at Ft. Worth, I came to the attention of one of the new piano faculty at TCU, Luiz Carlos de Moura-Castro, who I had met at Kenneth’s in Taos. I began playing sonatas with several of his students and coaching with him. He invited me to his home, where he had an active salon of visiting artists, local playwrights, authors, painters, and musicians. There I met some amazing people, including Radu Lupu and his wife of that time (her father had been the British Ambassador to the Soviet Union), who had studied in Moscow with Rostropovich and was in his class with DuPre. Luiz and his wife had studied at the Liszt Academy in Budapest, in addition to their native countries of Brazil and England, respectively, and had a wide circle of friends.

I also had a chance to coach chamber music with Ft. Worth and TCU’s reining Diva of the piano world (which is saying something, as it is the home of both the Van Cliburn Competition and Van Cliburn). She was a true force of Nature

Lili Kraus

At Taos the next summer, I met and worked with the Austrian pianist and then-president of Mannes School, John Goldmark, another Hungarian-Viennese pianist who escaped to the US. The first time I coached with him I was assigned a sight reading of a Dvorak piano trio. I did not know about the false treble clef, so I played it where I saw it. He was quite amused, and very kind. A wonderful artist. He had a habit of hiking on the weekend and sleeping out under the sky, and was an expert mycologist. If you are familiar with the local mycolological traditions, you might understand what that meant.

I began playing with the FW Symphony around that time, and continued my late nights in bars (i did not drink in those days!). Some of these experiences were unique; we had a steady gig on Sunday nights for a while at a cowboy bar (The Silver Slipper), and we played some pretty wild music, but they listened! We had a couple of other steady gigs, too, a campus joint (The Hop) and a jazz club downtown (Daddio’s). One of the bass players who passed through the band left at the same time I did, he to LA, me to Yale. He became the guy who taught Frank Zappa’s band his music for many years, and later worked with the survivors of the Doors. The drummer grew up playing with Stevie Ray Vaughn. Some great players passed through the band over the years, and it was a lot of fun.

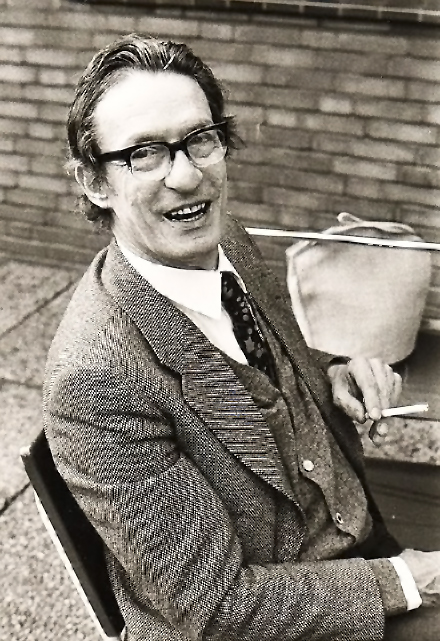

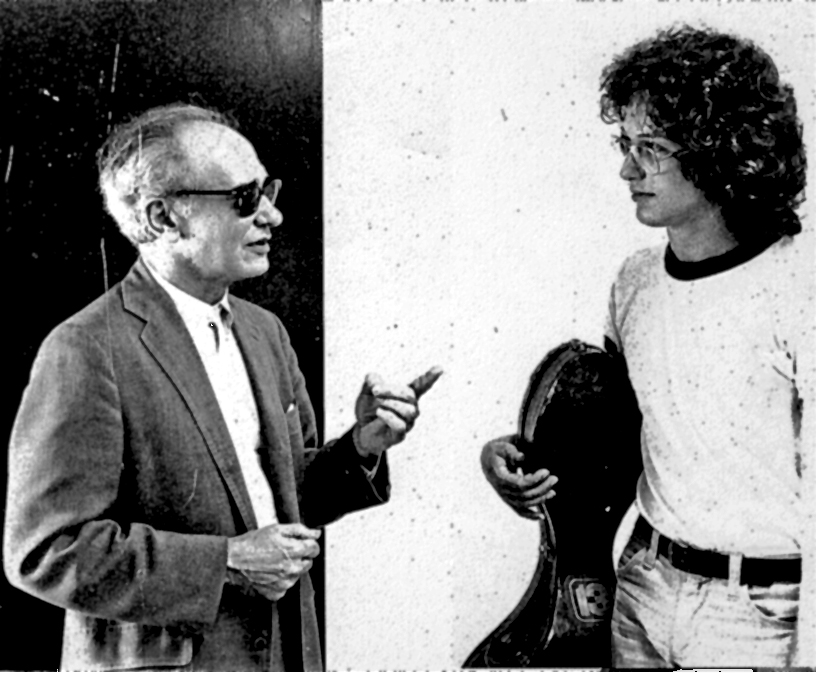

In 1974, I was invited to study at Cais Cais, Portugal with Antonio Janigro. Luiz had arranged to take a group of his students there to work with Yvonne Lafebure, and he managed to get me into Janigro’s class. (If you do not know who this woman was, look her up on youtube, there are some incredible master classes, another force of nature such as we no longer have among us!). It was an interesting time in Portugal, which had been mired in war in Mozambique, and had just had a revolution. As we arrived a week before Janigro was to begin his classes, and Sandor Vegh, the great Hungarian violinist (and Casals’ favorite) was giving masterclasses, Luiz arranged for me to play in his class. It was amazing. He had not studied the Brahms Sonata that I brought, but it did not matter. He taught me how his mind worked, and how he made music. He had me play a second time later in the week. When my turn came to play for Janigro, I brought the Hindemith Solo Sonata. He listened to the entire work without interruption. He then spent the next hour and more explaining his entire approach to playing the cello, and then segued into how to study music. He demonstrated at the piano. He played some Bach Suite excerpts, and then showed how Schumann harmonized them. He talked about the importance of understanding harmony and form. He demonstrated with my humble (but very good) German cello; how to sit, how to hold the bow, how to balance the left hand on the fingerboard, how to balance the right hand and arm on the bow. It was spectacular. He thereafter used my cello in class that day (I don’t know where his Guad was, he used that later in the week), and I sat behind him and could observe every detail of his bow arm. He taught me the bow hold I use to this day. He taught us all so much, so succinctly. More about this experience can be read in my blog post on Vegh and Janigro.

Above, Sandor Vegh and me, below, Antonio Janigro

The next year, back in Texas, I knew that it was time to leave. Janigro had invited me to Salzburg, but family issues (again) and my fear of not knowing the language were problematic for me. I went to Houston a few times to take lessons with Shirley Trepel (Principal of Houston Symphony and a former student of Feuermann and Piatigorsky), who was very encouraging in a tough kind of way; I really liked her and she was kind enough to understand that I could no longer remain in Texas. I made a tape and sent it to Aldo Parisot, who got me a scholarship to the Yale Summer program in Norfolk. The program began with a week of instrumental masterclasses before the chamber music and orchestral program got under way. Aldo’s wife, Elizabeth had to leave suddenly for a surgery, and one of her replacements was Thomas Schmidt, with whom I eventually formed the Arden Trio, which played together for 25 years. When Tom and I were about to play the Debussy Sonata in class, Elizabeth arrived and took on the piano part with no rehearsal and was fierce. Incredible. I attended the violin classes of Broadus Erle whenever I could, and I fell under his marvelous influence, as well. Aldo managed to get me accepted into his class at Yale for the fall with a scholarship, and so I finally left Texas for good.

The first time I went to play for Aldo at his home in Norfolk, I did not play a note. He sat me down and told me that he was going to tell me everything he had to say about playing the cello. In the following hour and a half, he started with how to sit, and went from there. There was a theme that ran through it all: balance. Using balance to release tension. Timing. Anticipation. I learned so much, yet to incorporate it all? I am still learning, 49 years later…

That summer, I made a trip into NYC with another cellist, who introduced me to Carlos Arcieri. We hit it off immediately, and when I moved to NYC a couple of years later, it was to an apartment on 57th St, 2 blocks from where he and Bill Salchow had their shops. It was a very sociable place in those days, as it was near some of the busier recording studios, Carnegie, and Lincoln Center, so people would drop by and chat, including players from the many visiting orchestras passing through town. And you could watch great artists at work, making bows, restoring instruments, trying out bows and instruments. A couple of years later, Bill decided to learn the violin, so he brought his grandsons with him to our apartment for violin lessons with the one who would become my first ex wife…

Well, back to Yale: the class Aldo had at the time was incredible. Students of almost every major tradition were represented: Starker, Magg, Piatigorsky, Tortilier, Gendron, Siegfried Palm, all with different approaches to style and technique, and master classes on Tuesdays would go on for hours. He also invited other cellists to give masterclasses for his class. While I was there, Starker came every year (they were close friends), and I also got to play for Pierre Fournier.

I had the opportunity to read string trios with the woman who would one day become my first ex-wife and Raphael Hillyer, played Shostakovich Concerto 1 with Otto-Werner Mueller, coaching the Brahms Double with Aldo and Broadus and playing it with the Repertory Orchestra, and started a wonderful quartet that worked intensively with Broadus as he was succumbing to lung cancer. The violist of that group, my dear friend and former roommate Jim Creitz, was the son of the cellist in the Pro Arte Quartet. He studied viola with Broadus while an undergrad at Yale, and went on to be Bruno Giurana’s assistant, joining the Quartetto Academica and later teaching for many years in Germany, where he had a quartet with Sadao Harada. Jim and I have remained close though separated by many miles and for many years. My family went to visit him and his family a few years ago at his home in Sicily, where he spent much of his time.

Broadus was an extraordinary and largely under appreciated musician, IMO. He had been a child prodigy playing in Vaudeville, with a typical tiger mom managing his career. He would play poker with stage hands, play some showpiece and come back to his hand while still a child. He then went to Curtis, where he was classmates with some of the greatest violinists America ever produced. He had some great stories of those years, which I have shared elsewhere. He moved to NYC and became one of the city’s great studio players and founded an incredible string quartet with Matthew Raimondi, Walter Trampler (later a founding member of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center), and Arthur Winograd, the New Music Quartet. Winograd left to form the Juilliard Quartet, and was replaced by Claus Adam, who left to join the Juilliard. He was replaced by David Soyer, who left to form the Guarneri. He was replaced by Aldo Parisot. During WWII, Broadus was a conscientious objector, and spent the war in prison. After the quartet ended, he went to teach at the Toho School in Japan, where his class accompanist was Seiji Ozawa. Broadus recommended him to his classmate from Curtis, Joseph Silverstein (the long-serving Concertmaster of the Boston Symphony), who got him an opportunity to study conducting at Tanglewood. And there hangs another story. When Broadus came back to the US, he brought two young violinists back with him, Syoko Aki and Yoko Matsuda . They studied with him after his appointment at Yale and they formed a music commune at his home in Connecticut with Richard Stotzman (the renowned clarinetist), Peter Salaff (later second violinist of the Cleveland Quartet), and Jesse Levine (bass player/composer). Broadus had taken part in Timothy Leary’s experiments during this time. Can you imagine any of this in today’s academic world?

Playing for Broadus was like playing for Yoda. He had thick, coke-bottle lens glasses and was surrounded by a haze of cigarette smoke from the multiple unfiltered Pall Malls he had going. He would listen with great intensity, and ponder what he heard at length before making very concise suggestions. He had a knack for knowing what you needed to know and giving you just that. I think of him often.

After Broadus passed away, Oscar Shumsky came to Yale. My future ex began lessons with him and he turned her technique completely upside down, which was fascinating for me as there was much to be learned from one of the world’s truly great musicians. He had been a student most recently and avidly of Dounis, and to hear of what he learned was most illuminating. My takeaway at this remove of many year comes to this: for the left hand, lifting the fingers is more of the effort to play than merely dropping them onto the strings. If you can’t vibrate, you are too tense. What does this mean? In the context of what I’ve been taught, it come down to to the freedom of motion one can achieve with proper balance of the body’s disparate parts. If the left hand is properly balanced such that the weight of the arm/hand is focused on the notes required, it is free to create tone that is voluptuous, austere, or sinuous, largely free of tension. If the right arm is properly balanced, the flow of tone is easily shaped with a variety of speed and textures. Greenhouse and Shumsky played together for many years in the Bach Aria Group. That takes us to my next chapter.

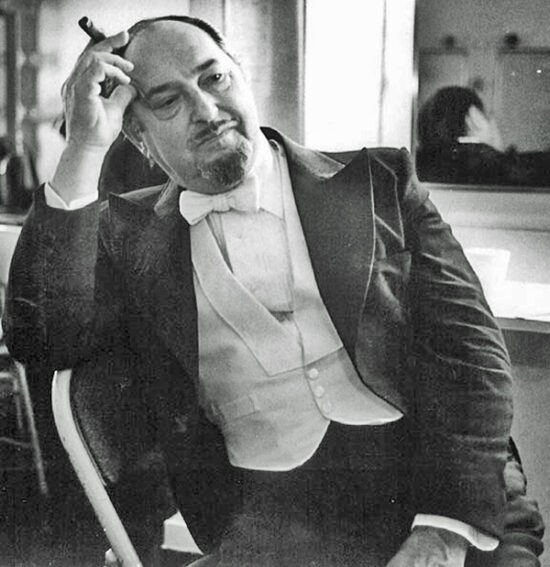

Bernard Greenhouse, as he was when I worked with him

I moved to NYC in 1977, where I came to study with Bernard Greenhouse. Of course, I wanted to be in that wicked city of that time, it was a magnificent fomenting mess of opportunity. When I first played for him, I stayed in the the apartment of Marin Alsop, who had been a friend of the woman who would one day be my first ex wife and mother of my first child. Greenhouse was so kind and welcoming, and accepted me on the spot. My first lesson with him, I played a couple of Sarasate transcriptions I had made, and he delighted in them, and told me of other arrangements he knew. When our lessons began in earnest, he had me playing Popper Etudes for a semester…. Hmmmm. We formed a wonderful relationship, and as I was pretty well trained by that time, and he was always on the road, I could play something different for him at every lesson thereafter. I was a smoker at the time, and we would smoke and talk and play. I was already working in the studios in NYC, where he spent many years as a freelance studio player, and had worked with a number of people I was then working for. He loved to tell stories! Lessons with him were amazing, he would demonstrate phrasing of such intensity and subtlety, the variety of vibrato (and its implementation) was astonishing (more on this elsewhere), and given with such generosity and ease. Funny thing, his approach to technique was also about balance. Balancing the body (large muscles over small, which he got from Casals) in all ways. Another funny thing is that I later made the majority of my career as the cellist in a piano piano trio. One of my first recording sessions at this time was for a record with the great sax player David Liebman, who played with Miles Davis. It was his first “solo” album, and the arranger was the cellist/trombonist and jazz great David Baker, who taught for many years at Indiana, and had studied with and wrote pieces for Starker. The bass player on the dates was another idol of mine from his years playing with Bill Evans, Eddie Gomez. Here is a track originally recorded in 1979.

Around this time, my first ex got a call from a retiring scientist from Bell Labs, who had founded an orchestra in Central New Jersey that was conducted at the time by Oscar Shumsky (the principal strings were what later became the Emerson Quartet). This gentleman had taken early retirement in order to return to his first love, the violin, and his second, tennis. As to the violin, Shumsky had recommended, you know… as a teacher. And so began another adventure in life learning. John Karlin had been a child prodigy in his native South Africa before settling into a storied career as a research scientist, but was a man of broad and deep interests. I loved talking to him about why vibrato made people sound louder, and at one point we were doing some research on that subject when he had to abandon the topic as his obsession with it was undermining his remaining time with the violin and tennis (as he got older, he started to develop both RA and macular degeneration). Anyway, he and his wife, Susan, came into the city often to the Philharmonic and City Ballet, and would take us out to their favorite fine dining establishments. John was a serious wine collector, and I learned so much about cuisine and wine from them. I’d always had a passion for cooking, and we would go visit them at their bayside home in NJ to hike, fish, cook, and drink, with long days and nights of great conversation. I was so fortunate to have known them… Funny thing, John basically invented the field of what the kids today call U/X. The Karlins were de facto grandparents to our son, Noah. Noah ended up going into U/X, and now is Product Owner at Booking dot com and living in Amsterdam with his wife and son. And he’s a really good cook! That apple did not fall far…

While at Manhattan School, I was first assigned to play in a piano trio for Arthur Balsam. The violinist was later Co-Concertmaster at the Metropolitan Opera, and we had a lovely time playing together that first year. The next two years of my time was spent playing cello sonatas every week for him. That was another great experience. Balsam’s career began as the child prodigy accompanist of the child prodigy Yehudi Menuhin, and he played with every great cellist of the mid twentieth century. He was a great sight reader, and delighted in listening to us first play whatever we brought in, and then offering a couple of suggestions to the pianist before pushing him off of the bench saying, “I will show you.” Then I got to play whatever it was with him. Playing a different sonata almost every week was a challenge, and I was always (and still am) on the lookout for unusual music, so this experience was absolute heaven for me. And the stories of all the great cellists! Funny thing is that Balsam had a piano trio for many years with the cellist Benar Heifetz. My principal cello over most of the last 40 years is a modern instrument modeled on his brothers Amati of 1622. Life offers us much if we choose to observe and learn from it!

I hope that all of this addresses Robert’s mandate in some way. It is important for us to remember those who come into our lives and shed light, and to pass that on to others.